From Luxury to Loss: Glimpses of a disabled man in the 19th century (audio & text)

Historical records contain rich descriptions of disabled people like Hugh Charles Smith: stories that are often overlooked and rarely contextualized.

Welcome to (Un)Hidden. I hope you will subscribe to this bi-weekly series and support this work if you have the means to do so.

If you would like to listen to this piece instead of reading it, you can listen here.

As a boy, Charles Smith ate his meals with ivory handled silverware, slept on a feather mattress in a mahogany bed, and woke each day to the love of family and community. He lived in wealth and privilege. But it didn’t last. A few months after his twentieth birthday he was sent to the Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Youth in Boston, where he spent the rest of his life ripped from his upbringing, living in increasing isolation, confinement, and anonymity.

When he died just shy of his 70th birthday in the summer of 1900, he had outlived not just the rest of his family, but the average American man by 24 years. In the often heart-wrenching records of the disabled dead—deaths vividly recorded as having been caused by gruesome accidents, violent abuse, preventable disease, and gross neglect—the town clerk’s register of his passing was simple. The oldest inmate of the oldest public institution for intellectually and developmentally disabled people in America, Hugh Charles Smith died of old age.

Within days of his death, Charles’ body was conveyed from Waltham to Alexandria, Virginia where he was laid to rest with his parents and three siblings. The Baltimore Sun made mention of the world that had disappeared since he left nearly half a century earlier. “The family was once a very large and influential one in Alexandria, carrying on several kinds of business on a large scale, but nearly all of them have now passed away.”

Smith’s fate rings out across time into the present day. Today as in the past, aging is one of the greatest threats to the health and safety of disabled people who find themselves placed under conservatorship, often institutionalized and alone, after the deaths of their loved ones. This reflexive turn toward institutionalization as a solution is deeply ingrained. At the Massachusetts non-profit MassFamilies, coaches ask parents to draw the ideal life they want for their kids, and more often than not, they unwittingly sketch the contours of an institution even though many are conscious of the fact that such places represent the worst possible future for their children.

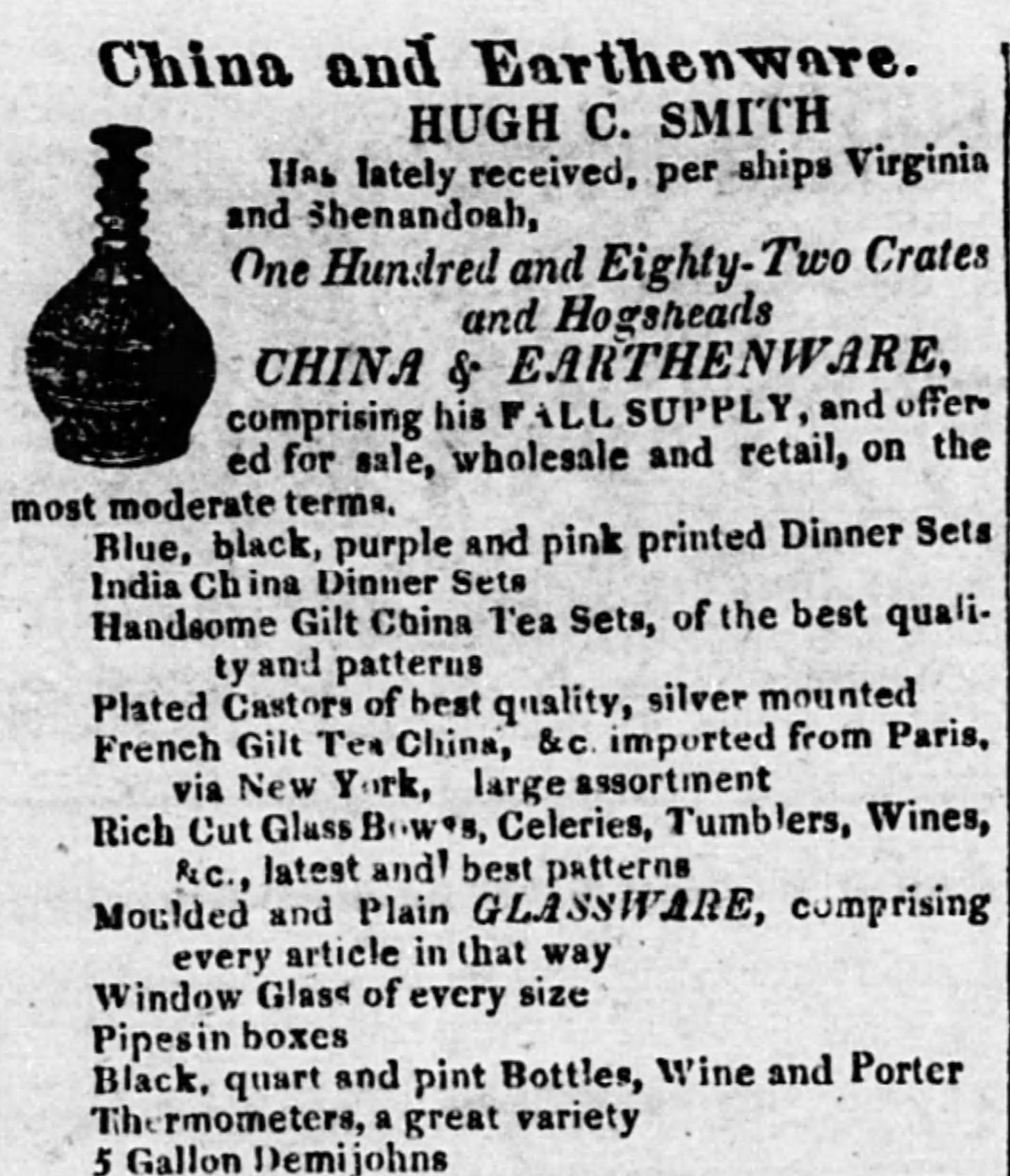

Charles began his life far from that outcome. Born in 1831, he carried the name of successful merchants who owned the Wilkes Street Pottery, a firm that was once synonymous with Alexandria’s place as a hub of American earthenware production. The family’s wealth ensured that his youth was filled with luxury, but it was also marred by loss. Three of his four siblings passed before the age of ten. In 1853 his mother died and a year later his father was gone, too.

H.C. Smith left clear instructions in his will. Everything should be done to provide for Charles. “I give and devise to my friend J.P. Milledge, and to my brother Richards C. Smith, the sum of twelve thousand dollars upon trust, to invest the same, and to apply the proceeds, or so much thereof as may be necessary, for the support and maintenance of my son H. Charles Smith, now at the school for the feeble-minded at Boston.”

In the mid-19th century, feeble-mindedness—a rough synonym for what today might be termed intellectual and developmental disability—was considered a source of hopelessness and woe. Americans believed that nothing could be done for so-called idiots, simpletons, and fools. In ways both sadistic and routine, the disabled were neglected and abused. But at that moment in history, the school named in H.C. Smith’s will stood apart. There, a doctor named Samuel Gridley Howe was experimenting with a radical notion. He believed intellectually and developmentally disabled people could learn.

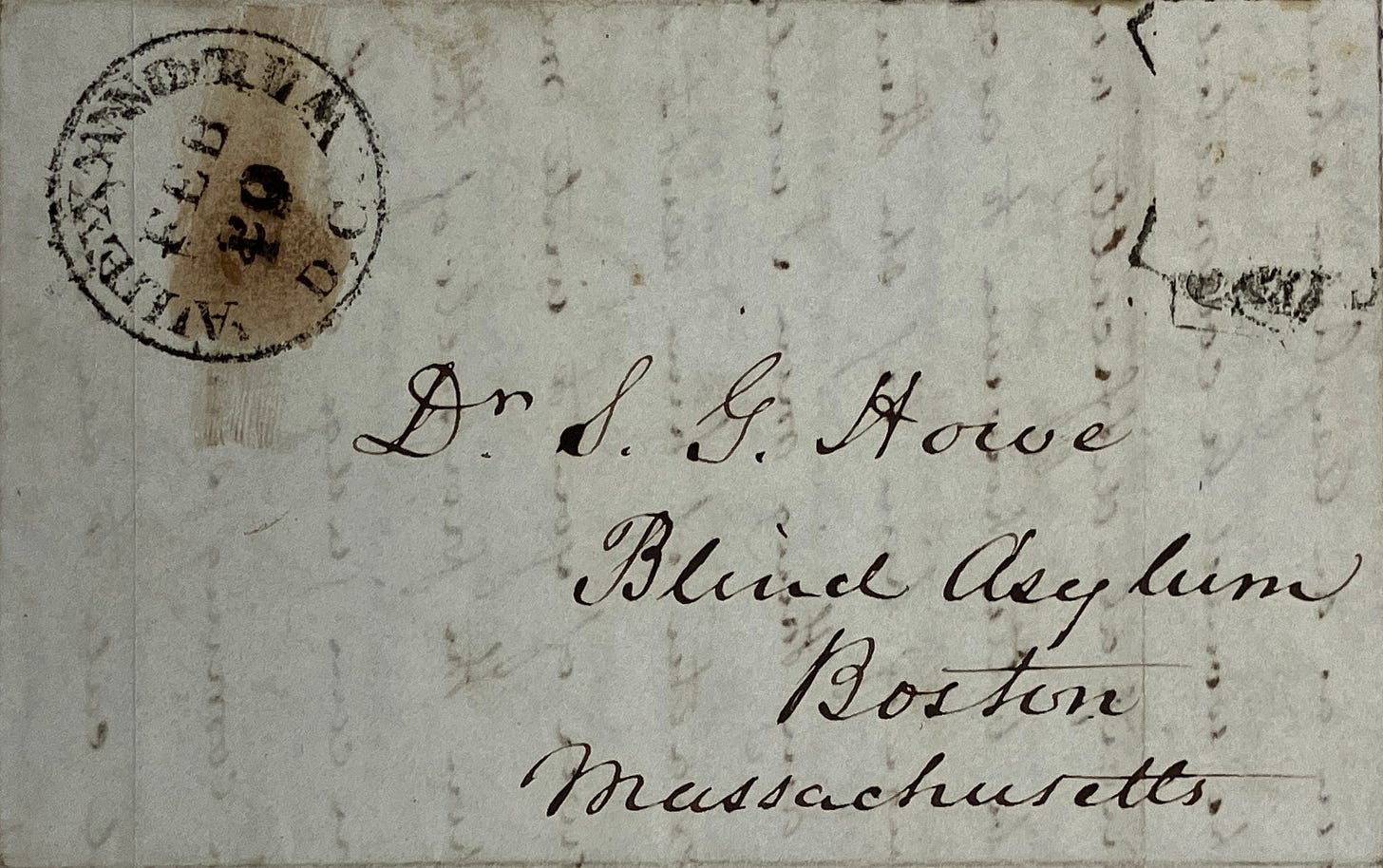

Howe was no quack. By the time he took an interest in intellectual and developmental disabilities, he had already upended conceptions about education and disability as the founding director of the Perkins Institution, the nation’s first school for the blind, and a highly-regarded center for disability work to this day. In the mid-1840s, Howe began to agitate for Massachusetts to make similar provision for intellectually and developmentally disabled children by creating an experimental school for them within Perkins. Opened in 1848, the project was a success and began to shatter preconceptions that the feeble-minded were beyond the reach of basic humanity.

The school received permanent funding from the state in 1851. A firm believer in public education, Howe called his students scholars and proudly noted that “this establishment is called a school, and it is a link in the chain of common schools.” His work would open the pathway for a new form of disability education.

Howe’s idea also created the segregationist boundary that exists today in the form of special education classes but in its time, it was a revolutionary idea and word of his school spread. Parents and siblings all over America saw something in their disabled loved ones that the rest of society did not, but few gained entry to the school. Howe was committed to accepting pupils from Massachusetts and surrounding states, many of whom came from destitute families. But from time to time, if a family was willing to pay private tuition, he knew their means could benefit the school, and he took their loved ones in. In the fall of 1851, Isabella and H.C. Smith made just such an arrangement and sent Charles to Boston.

By that time H.C. Smith had waited six years, hopeful that the school would become a reality and there would be a place for Charles in it. He exchanged correspondence with Howe and even made a visit to see him in Boston. H.C.’s love for his son was evident. He admired Charles’s precise memory, his passion for music, and his fascination with tools. Each summer he took the family to the countryside so that Charles could roam the outdoors.

“I believe myself he is susceptible of improvement – has many of the characteristics of that class,” he wrote to Howe in 1848. Yet H.C. also knew that the family could not spend all their days away from the city, and as Charles became a teenager, he grew increasingly worried about the their ability to provide for his well-being.

The Smiths could afford a personal caretaker for Charles, but the losses they had endured made them apprehensive at the idea of entrusting his care to one individual. In the oldest sense of the term, they wanted asylum for their son, and they sought it fervently, afraid that they would die before securing it for him. Their wealth and persistence paid off. When the Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Youth transformed from an experimental classroom into a permanent school, Hugh Charles Smith’s name was the first in the ledger.

In his first years at the institution, Charles would have lived the reality that H.C. hoped for, spending time outdoors, learning practical daily skills in the classroom, and living alongside peers roughly his own age. Howe’s curriculum was designed to teach his students enough where they could leave the school in relatively short order and return home with the ability to be self-supporting. By doing this, he ensured that the school remained a school, and with its successes, he was eventually able to establish it at a standalone site in South Boston, growing its enrollment to nearly 150 scholars.

Howe’s idea proved popular enough where a handful of other states followed suit, establishing their own schools for the blind and the feeble-minded in New York, Pennsylvania, Kentucky and elsewhere, but as he watched, Howe grew concerned that they were too large, had lost the character of schools, and were becoming institutions in the most concerning sense of the term. He voiced his belief that schools for disabled children should remain small and that pupils should leave when they reached the limit of their instruction.

By 1866, he had concluded that segregating disabled students in boarding schools was almost always a source of evil. “[A]ll such institutions are unnatural, undesirable, and very liable to abuse,” he told an audience in 1866. “We should have as few of them as possible, and those few should be kept as small as possible.”

But when Howe died in 1876, few of the institutional leaders elsewhere in the country agreed with his sentiment. They were busy building ever-larger permanent institutions where education was less a goal than wholesale segregation. His own board of directors lost little time following suit and in 1887, they hired a new superintendent to carry out their vision of moving the school from Boston to a spacious property in nearby Waltham, Massachusetts, where they could accommodate a permanent population.

Walter E. Fernald was a man with utopian visions. He agreed with Howe’s educational tenets and shared his view that society’s abuse and neglect of the feeble-minded was vicious, cruel, and an affront to God. But he believed that this was a powerful reason to reject Howe’s position on what was then called custodial care. Instead, Fernald felt that the feeble-minded needed institutional communities where they could be kept safe from the jeering eyes and cruel depredations of an ignorant, mean public.

Under Fernald, the institution grew from the small pair of buildings by the Boston waterfront to a massive complex on an ever-growing campus that would someday comprise nearly 200 acres. It would become the model for the world, and then fall into the forms of horror, cruelty, and abuse that Howe had warned it would. But that was still years in the future when Charles Smith died at the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded in 1900.

We know much of Howe’s story because it has been written about for more than a century, his papers carefully curated by his daughter and pored over by historians. We only know Smith’s story because his advanced age stood out among thousands of death certificates and ledgers I was able to review through the Massachusetts vital records which led to a handful of other available public letters and documents like H.C. Smith’s will.

But if there is a file or application for Charles at the Massachusetts Archives, we cannot know because Massachusetts blocks access to all patient data—and they consider Smith a patient rather than a student—in perpetuity without exception. Unless there is a change to these highly restrictive records laws which many states have to a lesser but still frustrating degree, it will always be difficult to know if there are documents telling more about Smith’s personal experiences in the institution. But annual reports and letters of the men and women who were entrusted with his care show how changes in American life washed over and forever transformed the safe harbor H.C. Smith sought for his son into something he never could have imagined.

In the postwar period, historians championed accounts of Howe’s disdain for institutions as proof that, all along, someone possessed insight enough to know that the shame of a nation—a network of large, segregated institutions where hundreds of thousands of disabled people were locked in squalor in the 1960s—was predictable and avoidable. Until now, it has been assumed that Howe held these beliefs as universal, meant them without exception, and never wavered. At the heart of that myth is the idea that he never kept a pupil for life.

Smith’s story shows that this assumption was incorrect and that matters, not as a historical purity test of people like Samuel Gridley Howe but as evidence of the need to see fuller disability histories with disabled people in them.

As long as we are prevented from having complete access to these histories, it can be difficult to name anything with certainty. What is clear is that Charles Smith was loved by his family and that the school entrusted with his life—the Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Youth—became the opposite of what his father and Samuel Howe envisioned. At the time of Walter Fernald’s arrival at the school in 1887, it was nationally recognized, not as a utopia, but as a disgrace for Walter Fernald to fix; overcrowded and staffed by violent predators.

It would be easy to relegate this history to a bygone era, but we see its tendrils in places like the Judge Rotenberg Center, which affixes shock devices to autistic kids at its facility in Massachusetts today; or Shrub Oak in upstate New York, an “unregulated boarding school” cited for its rampant abuse of autistic kids in ProPublica earlier this year; places where parents are promised that the full humanity of their children will be seen and respected, only to see it abandoned in favor of a cruel efficiency at best.

Seeing these connections is essential if we are to confront the ideas and actions that hold us back from a world where disabled people have true equality. To that end, if we are going to understand that our actions and beliefs today are rooted in history and shaped by those who came before us, we have a responsibility to see them all, from the Samuel Gridley Howes to the Walter Fernalds and most importantly the Charles Smiths; disabled people whose lives can be seen and understood, and who have so-often been overlooked. “(Un)Hidden: Disability Histories and Our World” is about doing that.

A Glimpse Inside the Research Involved in This Story

I first came across Charles Smith’s name during an attempt to catalog deaths at the Massachusetts School from the Feeble-Minded from 1887-1924. Due to restrictions in Massachusetts, the only way to do this was to look at every death certificate and register for the City of Waltham during this time. When I saw Smith’s age at the time of his death, I was immediately intrigued.

When I went looking for more information, I found that the state had accidentally digitized the ledger book of inmates from the institution and was surprised to find Smith’s name at the top of the list in the year that the school shed its status as an experiment.

All of the the institution’s other administrative records are located at the Massachusetts Archives and through a legal challenge, I was able to gain access to review them with some stipulations, including a prohibition on seeing the names of inmates. To add to the challenge, the collection of approximately 60 boxes (250,000+ documents) is entirely out of chronological order from page to page, ranging from 1848 to the 1990s.

However, over the course of my ten years of archival research, I was able to locate a letter from H.C. Smith to Samuel Gridley Howe in 1849 because Smith was not an inmate and his name was not redacted.

In Howe’s papers, located at the Houghton Library at Harvard University, I found the most important document; an 1848 letter from H.C. Smith to Samuel Gridley Howe describing his hopes for his son.

Additional research, books, and papers helped to round out the piece, including James W. Trent Jr’s biography of Howe, The Manliest Man and Sharon Murphy’s Banking on Slavery.

A note about language: When describing disability in present day terms, “(Un)Hidden” uses disability first language. For example, instead of “persons with disabilities” it uses “disabled people.” This is a deliberate choice by the disabled author of these pieces. In using historical terminology, given its lack of present day synonyms, the original terms are preserved, despite the fact that they are often horrible words to encounter. Inevitably there will be occasional mistakes or inconsistencies to this or any approach to confronting these terms.

Some notes about the possible connections between H.C. Smith and S.G. Howe:

The exact relationship between H.C. Smith and Samuel Gridley Howe is unclear. The Smiths were referred to Howe through two intermediaries, a “Mr. Graley” and a “Dr. Palfrey” who were, in all likelihood, the ministers Alfred Graley and John Gorham Palfrey (one of Smith’s brothers was also a minister). Palfrey was an ardent abolitionist, represented Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress, and was well-acquainted with Samuel Gridley Howe.

Howe was one of the nation’s leading abolitionists and would later flee to Canada briefly in the runup to the Civil War after being outed as one of six key backers of John Brown’s takeover of the federal armory at Harper’s Ferry.

Living in a slave state, Smith’s record is more unclear. He died providing a pathway to freedom for Addison Webster, his enslaved “servant” but did not free him. As a member of the American Colonization Society, he also supported the racist notion of sending freed slaves to Africa. At the same time, he contracted with at least one prominent potter through his firm and according to the historian Sharon Murphy, once “paid $600 to prevent the breakup of a local slave family” who were later found to be free and thriving in Washington D.C.

While their positions seem disparate today, so few well-to-do white Americans held any anti-slavery sentiments in the early-mid 1840s, they may well have seen connections that drew them to one another. An 1849 letter from Smith to Howe is suggestive but inconclusive. Smith refers to a request from Howe to assist him in looking for a sizable plot of land in Washington D.C. at a time when Howe’s close friend, education reformer Horace Mann, was serving in the U.S. Congress and abolitionists were aggressively advocating to end the slave trade in the capital. The compromise of 1850 would ultimately bring about an end to the trade, but not to the ownership of enslaved people in the capital. Still, their dealings could have been related to an entirely different matter and require further research.

Great to discover your substack! I've been following Charles Smith in my own records for some time, but have never had an opportunity to find anywhere near your level of detail. So great to have a chance to learn more about him. (We also have wonderfully different takes on Samuel Howe -- https://naomischoenfeld.substack.com/p/profiles-angeline-arms )

The photo you used as the thumbnail for this confuses me greatly, as far as I know the institution was sharing the grounds along with the Perkins School, which was comprised of a handful of buildings contained within East Broadway, H Street, G Street, and East 4th Street. And I don’t believe I’ve ever seen these two buildings in any photos of Perkins, there is talk in the 1869 annual report of the School for The Feeble-Minded of buying properties in South Boston, but this might be in relation to buying 546, 548, 552 and 554 E 4th street? The other part that’s confusing me is that the same photo has the subtext of “The first home for the feeble-minded at South Boston” and is being used in reference to a private institution.. Also founded in 1848 by a John Hopkins, on another website?? I’m so very confused, sorry.