Nazi Ideals and the Disabled Inmates of Oregon's Fairview Home

The third and final installment of (Un)Hidden's series on disabled inmates who escaped from institutions

Inmates of the Oregon Fairview Home—the state’s 968-person institution for intellectually and developmentally disabled people—were not allowed to leave its sprawling campus near Salem, and visitors rarely came to them. Still, word from the outside world made its way to them each day in newspapers and magazines.

On March 12, 1936, a banner headline in the Capital Journal greeted them with the announcement of France’s treaty with Russia and defiance of Nazi aggression. Below, a small item noted that bears were emerging from hibernation at Crater Lake, while another described Franklin Roosevelt’s use of the new presidential yacht for a vacation. Much to their surprise, just below “France Firm Against Germany,” dead-center at the top of the fold, there was also an article all about them.

Surprise quickly turned to panic. The head psychologist described a “pitiful” chaos and pleaded for help. “The inmates are badly excited,” she said, “and we may have trouble unless they can be calmed.” In the commotion, five inmates—Wallace Fisher, 23; Robert May, 24; Alfred Riggs, 18; Edward Davis, 22; and Percy York, 17—ran for their lives. The ones who remained begged to know if the headlines about “mercy killings” were true. Was the institution going to murder them with chloroform?

No state plan had been put forward for the killing of the so-called feeble-minded, but killing the so-called feeble-minded is just what was being discussed in a sociology classroom at nearby Willamette University, one of the nation’s oldest and most prestigious private academic institutions. There, Professor Sceva B. Laughlin and his students had reached a point of agreement: the feeble-minded should be killed. “One has only to visit the Oregon state feeble-minded home and look at those children lying in bed unable to lift their heads to agree with me that they should have been chloroformed,” Laughlin reportedly said.

In the weeks that followed, the story of Laughlin’s proposal and the inmates’ escape were national news. John O’Rafferty, pastor at Lansing, Michigan’s St. Mary’s Church said the idea was “positively unethical and it violates the natural law of God.” If carried out, O’Rafferty said it would be murder. William Pritchard, the superintendent of the state asylum in Columbus, Ohio agreed. “I am unalterably of the opinion that the states should care for these cases,” he said, in opposition to the idea of killing.

In a historically rare instance of reporting inmates’ views from within an institution, the men at the nearby state asylum, the Oregon State Hospital, got their say, too. In a straw poll taken by the inmates, 100% of the participants rejected the notion of killing the disabled. The Oregon Statesman Journal published unconfirmed accounts of one inmate who remarked, “If all the feeble-minded persons were chloroformed it would fill the graveyards rapidly and I wouldn’t give much for the chances of Dr. Laughlin’s survival.”

But Laughlin’s comments were not universally denounced. Far from it. “We’ll be the ones who’ll have to deal with this issue in future years, and we intend to settle the matter in our minds in this classroom, if possible,” his students told the Oregon Daily Journal. Reed College anthropologist Alexander Goldenweiser, said the idea was “humanitarian.” Oregon Governor Charles Martin thought, “The theory is a fine thing in principle. Civilization must find some way to best deal with this distressing situation.”

While tipping their hats to Laughlin, some sought to downplay the seriousness of the proposal. University of Washington doctor J.F. Steiner called the idea “humane” and “sensible” but also “impracticable because of public opposition.” Salem Capitol Journal editor George Putnam said the uproar was nothing but “callous sensationalism,” and pointed to the fact that “Euthanasia in such cases has been advocated for many years by eugenicists and actually practiced in some countries.”

As coverage of the incident spread, authorities were steadily tracking down the escaped inmates. Within a matter of days, four of the five were captured and returned to the school. But the disquiet continued at Fairview, where the inmates were not calmed by attempts to reassure them.

For his part, Laughlin was pained. The son of a Midwest farmer, he was a dedicated educator who used his prestigious academic post to advocate for progressive causes. A Quaker, he was described by one Salem clergyman as an “ultra-pacifist.” How then, had he come to be so misunderstood?

“The Burden of the Feeble-Minded”

Sceva Laughlin’s remarks may have been a source for outrage, but his defender, the editor George Putnam, was correct when he said that they could hardly be considered shocking. For thirty years, America and the United Kingdom had been the world’s center for eugenics. And while the pseudoscience of “better breeding” became (and continues) to be an ideological watering hole for a host of hate-based philosophies, its wellspring was always its vicious dedication to wiping out the disabled through segregation, sterilization, and euthanasia.

In the 1920s and 30s, eugenics lost ground in some academic and social circles where it was first championed, but more than anything, it became so widespread, casual, and diffuse in American society that people ceased to notice as it burrowed into the national consciousness. The tools of eugenics, especially public fascinating with intelligence testing and IQ scores, became fashionable. The words of eugenics—particularly the term “moron”—became part of the common vernacular.

These crass forms of amusement were backed by laws like the federal anti-immigration laws of the early 1920s and the Supreme Court’s pro-sterilization Buck v. Bell decision in 1927. As a result, eugenics was always in the background and this provided its more fervent supporters like Sceva Laughlin with an ever-present, wholly acceptable way of pitching their ideas to the public.

The Great Depression only helped them make their case, because people became fixated on people who needed social supports. Eugenicists had always used economic arguments to argue that disabled people and their ancestors were costing states more than they contributed. Now, that cost-saving argument had fertile ground to thrive.

In short, by 1936, segregation and sterilization of disabled people was an everyday part of American conversation and life. That year, prisoners in Oklahoma rioted against proposals to have them sterilized while the wealthy heiress Ann Cooper Hewitt brought charges against her step-mother for having her sterilized as feeble-minded without consent.

Americans were also more accustomed to the idea of “mercy killing” than we like to think today. In the 1970s, Eunice Kennedy Shriver would expose the frequency with which doctors and parents allowed disabled infants to die based on the opinion that their lives were not worth living. But the roots of this practice extend deep into American history in malevolent and heart-wrenching ways alike.

One newspaper account from the mid-1930s captured the prevailing mindsets:

“Feeble minded persons have no divine place in the scheme of things. They are here because man has not ordered his life as he should. Dissipation and disease have weakened great numbers of men and women, and over a period of centuries the cumulative effect has been the appearance of a vast number of persons constitutionally unable to maintain themselves or to take any place in the society of their fellows.

The number of these unfortunates constantly increases, as they reproduce and as those who are but border-line cases marry similarly situated mates and produce definite defectives.”

It was in this context that Laughlin instructed his students to look into the financial “burden” of the disabled inmates in Oregon’s school for the feeble-minded and state asylum for the insane. Going back generations they used hearsay and speculative diagnosis to conclude that one family had cost the state $12,000 (a large sum at the time) and that the state institutions would save $300,000 per year by killing the disabled.

When reporters expressed interest in his conclusions, Laughlin was shocked. To him, the whole affair was a series of misunderstandings on the part of the feeble-minded and insane. So he conveyed a message. “As far as chloroforming suggestions go, they do not apply to anyone able to read a newspaper or run away,” Laughlin said. “I mean the mercy killing idea to be applied to idiots who could not read, talk or understand.”

Moreover, Laughlin echoed what many of the experts who had denounced him had said. The nation was not ready for such things just yet. “The suggested plan of chloroforming will not be carried out in this generation or the next, but it will serve to place before the nation the tragedy resulting from certain types of marriage.”

From the outset, he said he was surprised by it all. “I’ve been talking like this for years.”

Instead of paying attention to his euthanasia comments, he said he really wanted the state to pass a marriage control law to force couples to present themselves before a doctor or state board to evaluate their heredity before allowing them to marry. Then, euthanasia would never be needed because the state would sterilize existing disabled people and prevent new ones from ever being conceived.

A German-American Playbook

Sceva Laughlin’s comments worked and word from the state’s institutions was that the inmates had quieted down. Meanwhile, Laughlin kept pushing a marriage restriction law. In a massive article in The Oregonian the following year, he provided the hereditary charts for a sweeping eugenic piece about the societal burden caused by a German couple, an indigenous woman, and others. Oregon already had laws preventing inter-racial marriage and requiring a waiting period for all marriage certificates. In November 1938, Oregon voters went to the polls to add eugenics to the mix. 243,915 voters backed the proposal. 59,301 opposed it. Laughlin got his law.

Laughlin’s explanation to the inmates two years earlier was forgotten, but in light of his argument that his remarks were actually geared toward passing the marriage law—not killing inmates—it reveals a true believer who was also willing to stretch the truth to get his way. After all, Laughlin must have known that under state law, 957 current and former inmates of Fairview had already been sterilized, many as a condition for release.

It seems more likely that Laughlin was using a political playbook of sorts. Much of it was on display at Willamette in 1935—the year before his euthanasia comments—when he celebrated the arrival of “Eugenics in New Germany” a traveling exhibit championing Adolf Hitler’s government policies, sponsored by the American Public Health Association and Germany’s Deutsches Hygiene-Museum. By then, Hitler’s Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring had been in place for two years and the Genetic Health Courts it created had sterilized 134,100 people.

Laughlin’s interest in German eugenics was no passing fancy. As early as 1925, he was forging connections across the Atlantic, hosting a talk for his Willamette students with Austrian reproductive specialist Dr. Hans Leonhartsberger, who was an early proponent of Germany’s annexation of Austria.

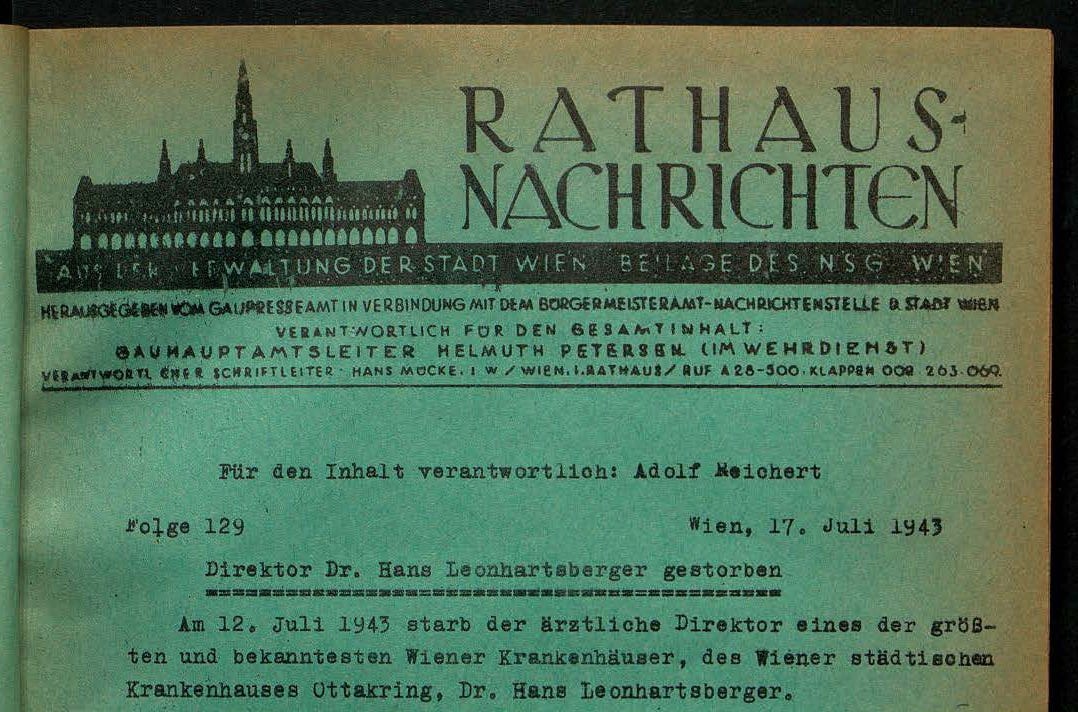

Under the Nazis, Leonhartsberger would become the director of a major Vienna hospital, the Wilhelmina Hospital, as well as the acting head of the Senior Government Medical Council. His 1943 obituary celebrates his 1937 arrest and beating by Austrian officials for his unwavering support of the Nazi takeover that occurred the following year.

Leonhartsberger was hardly Laughlin’s most significant connection to Nazi eugenic policy. When the 1937 article using Laughlin’s work appeared in The Oregonian, he proudly mailed a copy off to Harry Laughlin (no relation), the head of the Eugenics Research Association in Cold Spring Harbor, New York. Harry Laughlin replied, praising the article and Sceva Laughlin’s work. “I feel that the matter is excellently handled and I congratulate you,” he wrote, enclosing information on other eugenics efforts afoot in America.

Perhaps no figure in America was more significant in providing the Nazis with American eugenic ideals than Harry Laughlin, an epileptic who had nevertheless been a standard bearer for the most extreme eugenic ideas in America, and an evangelist for laws putting them in place, since the early 1910s. When Congress passed the nation’s most restrictive immigration laws in 1924, Laughlin was their resident eugenics expert, furnishing data to support the racist allocation of immigration quotas. In 1936 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg for promoting race science.

Perhaps most importantly, Laughlin authored the Model Eugenical Sterilization Law that was used by the Nazis when they wrote the 1933 Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring. The law set a baseline for policies to come. In 1938, a German couple petitioned the Nazi government to allow for the mercy killing of their developmentally disabled infant. The request provided leaders with the pretext to begin moving toward implementation of what became the Aktion T4 program in September 1939. Under that program mentally disabled people became the first victims of the Nazi Holocaust, and the methods used to kill them in the German disability institutions were eventually used in death camps.

Sceva Laughlin died in 1947 knowing where the policies he advocated for in Oregon had led in Germany. Further research will be needed to know what he made of it all, but one thing is certain. His marriage restriction law lasted longer than the Nazis and was one of the many vestiges of the first waves of American eugenics that set the baseline for America’s postwar embrace of the idea under other names. By 1954, forty states had blood test requirements for marriage and as this series will continue to note, America’s institutional inmate population of intellectually and developmentally disabled people peaked in 1967 at more than 230,000.

Because people like Laughlin were never held to account, their ideas melded seamlessly into American life and it is the accumulation of these kinds of policies that have so deeply reinforced the kinds of thinking that this series sought to explore from the outset: the present-day belief among the non-disabled that disabled people are inherently unable to understand and accept forms of care that are actually violence; and the idea that disabled people are unstable in ways that require organized, often state-sponsored violence to keep them from asserting equal rights.

At the same time, the Oregon uprising is just one of many historical examples showing how a substantial segment of American society knew they were playing with the idea of mass extermination of the disabled in the runup to World War II. From journalists to politicians and professors, nearly everyone was caught up in it at the time. It is telling that the only people who seem to have truly understood the full credibility of their threats were the disabled inmates who spoke out, the disabled inmates who rose up, and the disabled inmates who dared to escape.

*Special thanks to Annie Moots, Digital Collections Librarian at the Pickler Memorial Library at Truman State University.