"She has a right to learn stuff"

A mother's quest to uncover the origins of the IQ test her disabled daughter was required to take.

Listen to this week’s edition of (Un)Hidden or read on below.

The best hour of my week was spent on Zoom, chatting with a brilliant, funny, talented 12-year old named Louisa. In that one hour I was treated to a song Louisa is rehearsing for chorus, got a book recommendation (she highly recommends Robert Beatty’s Serafina and the Black Cloak), chatted about her love for math class (In her words, “I can do complex calculations”… a skill I have never had), debated the best kind of pie, and discussed the excellent quality of the questions from her classmates earlier that day when she ran a session to educate them about Down syndrome, which she has.

What a stark contrast to the ugly hopelessness spit out by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. the day before, when he asserted that another group of intellectually disabled folks, autistic people, lead lives that aren’t worth living.

This contrast has played out for more than a century.

While disabled people try to lead our lives—which are worth living—hucksters like Kennedy have consistently used us for their own ambitions to be seen as smart and powerful. Often, they have done it by creating arbitrary criteria about what makes a good or normal human being in their mind. Then they demonize the people who can’t meet those criteria as bad or useless, and they exploit them (and their loved ones) to push an agenda, usually by claiming that there is a crisis that only they can solve. For Kennedy, the criteria are a bizarre list of skills ranging from the ability to pay taxes to the ability to write poetry. The results don’t support his beliefs (autistic people pay taxes and write poetry), so he just makes up the conclusion, which is the assertion that autism is a great tragedy and only he can find its cause.

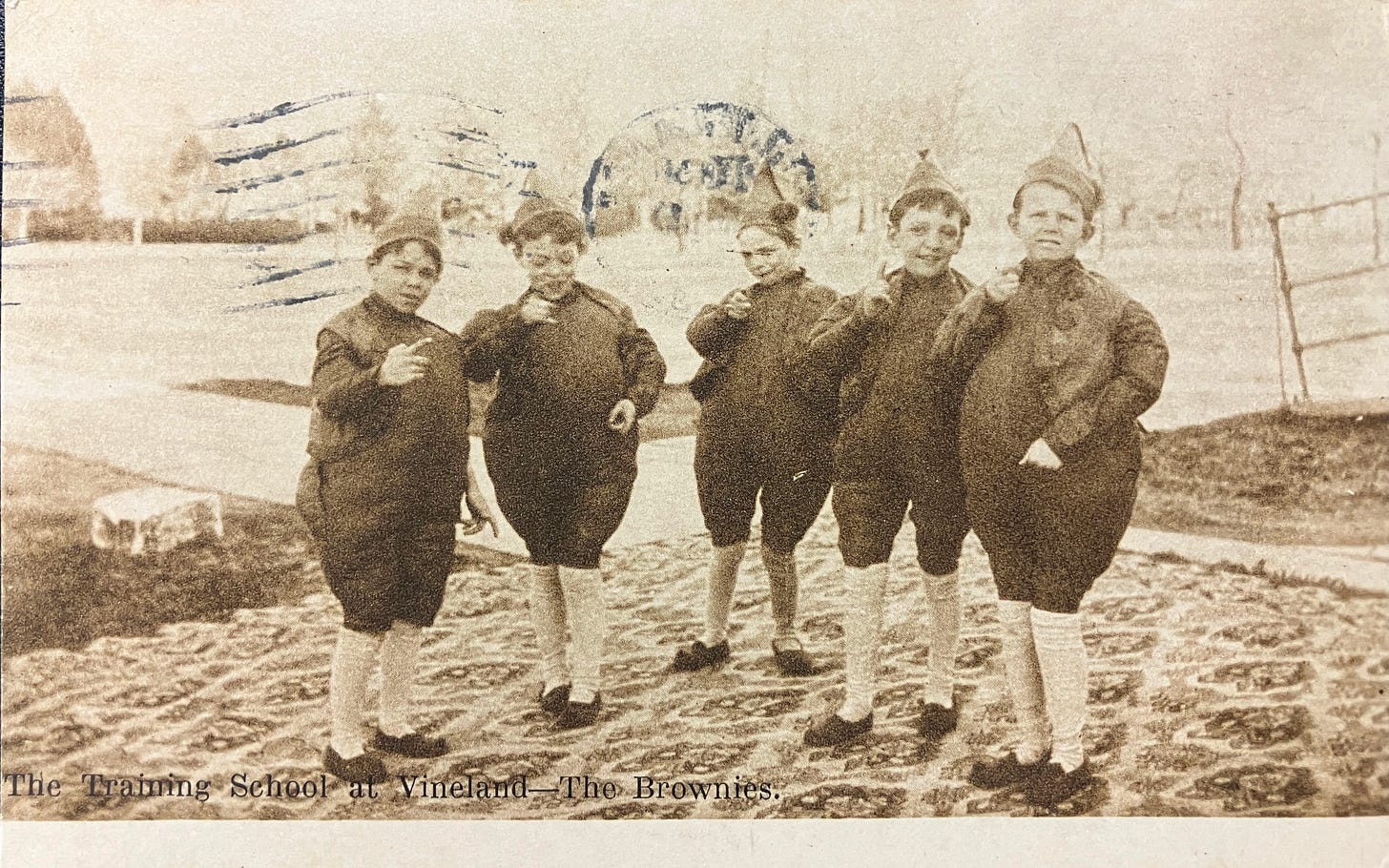

In the first decade of the 1900s, psychologist Henry Goddard was in the same spot and did the same things. He wanted to be seen as smart and powerful and like Kennedy, had little proof up to that point in his life. Using a set of arbitrary questions derived from a test he’d picked up in Europe, Goddard tried to measure intelligence, experimenting on a captive, institutionalized population of disabled kids in New Jersey.

Declaring that the ones who failed the test were a new kind of disabled person called a moron, Goddard then went out, tested lots of other people, led a generation of similarly unimpressive folks in further developing what became the IQ test, and then declared a national crisis of stupidity (I mean this quite literally). His recommendation was the segregation and sterilization of people who failed the test. Ever since, the IQ test has been the tool of cruelty, abuse, and oppression used against disabled people, with horrifying consequences. Today, it shapes our conceptions of intelligence which are dangerously narrow and brittle.

Nobody knows this story better than Louisa’s mom, Pepper Stetler, author of A Measure of Intelligence: One Mother’s Reckoning with the IQ Test. Stetler is a professor of art history at Miami University. After Louisa was required to take an IQ test to qualify for services, Stetler put her research expertise into a massive project to understand the largely unknown history of Goddard and crafted this poignant and powerful work of history and memoir.

Goddard’s story is also a prominent facet of my recently published book, A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled, so I’ve wanted to catch up with Stetler who has made brilliant connections between past and present. Those connections are what (Un)Hidden exists to make, so while Louisa went to work on a science project in the kitchen, I chatted with Pepper about the IQ test and the ongoing, widespread segregation of disabled children that began in public schools with Walter Fernald and Henry Goddard.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Alex Green (AG): When you went looking to understand the roots of the IQ test, you went to the archives of Henry Goddard, who brought the IQ test to America, developed an English version on the disabled inmates of the New Jersey Training School (later called Vineland), and used his findings to coin the word moron in 1909. What was it like to go from this world into the language and images of disability in that world?

Pepper Stetler (PS): The Goddard archive is at the History of Psychology Museum at the University of Akron, and it is a pretty weird place. There's a very small museum on the bottom floor that has a kind of pop psychology museum approach to it. Then there are archives on the second floor. There were lots of photographs that were really hard to look at and really awful, mean spirited, and abusive reports. I felt angry that nobody had reckoned with this. Like, I feel like as a country we have not talked about this enough. We have not reckoned with what this still means to our world and how the legacy of it plays out in lots of different ways today. Those things are even more apparent to me now than they were five years ago when I visited the archive.

AG: Some of the terms in this history are offensive because they’re old but you mention the mean spiritedness, and that’s definitely clear in so much of how people wrote and talked about disabled people. What do you make of that mean spiritedness? Was there a moment in your research where that hatred clicked?

PS: There’s a difference between unsavory language and finding a report where, you know, someone is beaten because they're screaming in the middle of the night, or locking somebody in a room to watch if they're “intelligent enough” to figure out how to leave. Those kinds of things are just cruel and it’s clear that the person doing it doesn’t think these people are human. They think disabled people are almost a different species. That kind of eugenics mindset of it all is really difficult.

AG: Louisa, your daughter, took IQ tests before you started this research. Once you began looking into the history, did you feel angry that the test was still used or guilty about having Louisa take the test?

PS: There are all sorts of ways in which I think about it in the sense that, it's made me live with the fact that the world is a very, very messy place. It is not all black and white in the sense that every person who wants to give Louisa an IQ test is not a eugenicist. But at the same time, it really makes me angry that this is still used. I don't think psychologists have reckoned with the history of this. I'm an art historian, and art history has a pretty terrible, background to it. We stole stuff from lots of different places in the world, but I just feel like other fields hide behind science a lot. For that reason, there's a lot that's covered up and not reckoned with and considered about this.

On a more practical level, it’s not so clear cut for me just to refuse and tell the schools not to give her an IQ test because this compromises her ability to have an IEP (individualized education program) which connects to qualifications for services later in life.

There's a way in which undoing this is almost more than I can see. It's so much more complicated than just saying “we're not going to use this test anymore.”

AG: It’s part of the way that our world thinks about intelligence whether you've had an intelligence test or not. Our notions of what intelligence is are built on the ideas of these sort-of petty scientific quacks who were looking to build out their careers. Do you have a sense of a better way to think about intelligence? Does it matter to have a better way?

PS: I don't know. I get to the point in which it's not as if I am saying that IQ tests are flawed or there are errors in them. For what intelligence tests are trying to test, they're actually pretty good at measuring that. But the issue is with how we have defined intelligence. There are various definitions of intelligence by psychologists that are, you know, about decision making and planning or understanding information and responding to it.

But there's also ways in which intelligence has created a culture of competition. It has created a culture in which intelligence is used for power. A culture in which we have distorted things, where intelligence is being good at tests. And we've forgotten that tests were supposed to test something, right? Like, they were they were supposed to have a kind of substance to them beyond just being good at a test. It has corrupted learning. It has corrupted what we value in education. It's corrupted what students expect from education.

AG: Where can we see that happening in this disability history?

PS: For Goddard, the IQ test informed this whole idea of special education: that we have to identify in order to segregate. If we can't put these students in an institution, then at least put them in a separate class. Then you look at the state of special education these days and the whole system is like that. The normalization of segregation, just like Goddard, that's what's natural and normal for some school districts.

AG: I was astonished in my research to find how far back the terms “special” and “exceptional” were used to talk about disabled people. Those words are common today, but you don’t use words like that in the book and I was curious why.

PS: That's interesting. I don't think I consciously made that choice, but I'm not surprised I didn't use it. In the words of Simi Linton, why are some people's needs special? Why can't everyone's needs be seen as needs? It's a euphemism that covers things up, like the special needs classroom. I like the term segregated class because it puts the emphasis on the civil rights issues of it. It emphasizes it as a form of segregation.

AG: You write that your vision of a great life for Louisa is one where she can serve her community, and her community can serve her. That's a powerful vision of the world. What do you think folks should be doing right now to make that kind of vision reality?

PS: I think you make space in businesses to hire people with disabilities. You focus on figuring out what you need to get that done. I don't think most people in the world even understand what would need to happen. It's not a matter of just creating an inclusive classroom. It means thinking seriously about how people with disabilities can be supported through employment.

AG: As a parent of a disabled daughter, what has studying this history done for your understanding of the world? Is it helpful? Harmful? Both?

PS: It's made me see people's value to the world differently, in ways I don't think I would have bothered thinking about before I learned about this and had Louisa as my daughter. It has especially changed who I think education should be for. I now much more strongly assert the right of everyone to an education, whereas before it was like, “well, if you can do this then you can belong in this classroom, you have to clear a bar first.”

Now, I don't care if Louisa clears that bar. She has a right to learn stuff. And even if it looks different than what most kids are able to express or show about what they know, I don't care. Everyone has a right to learn in their own way. That means in school. It means in college. It isn't up to us to measure that. It's up to us to provide that.