The Disabled Inmates Who Dared to Escape

The first in a three-part series about disabled people who fled violence that society demanded they accept.

One of the sadistic paradoxes of modern American life is that disabled people are disproportionately victims of violence because of the widely accepted lie that they are more likely to be the perpetrators of it. From Australia to America, much of that violence comes at the hands of the state, and is often directed at intellectually disabled people of color.

[A NOTE: Email subscribers, please open this in your browser for a full reading.]

Acting on the demands of non-disabled people who often choose to interpret the differences in others as a potential danger, elected leaders have spent recent years dedicating substantial police, judicial, and even military resources to chasing down disabled people in public places, with horrifying consequences. Just type “police shooting autistic” into a search engine and look at the many results.

The fact that we respond to the public presence of disabled people with violence is not something we like to talk about. Instead, non-disabled folks (and plenty of disabled ones too) often have a trusty anecdote at the ready, describing how their encounter with a disabled person—usually someone with a cognitive disability —justifies an America where we turn the tools of last resort on the disabled first.

These widely-held prejudices are based on ancient superstitions. They were brought into the modern era by early 20th century psychologists, doctors, legislators, and reformers who saw disabilities as a form of defect. Based on that connection, they then used mountains of faulty data to make a powerful and fraudulent scientific claim: The most common biologically-dictated, innate expressions of defect—and therefore, disability—are delinquency. Want to find the people responsible for mischief, crime, and unbridled sexuality? Wondering why American civilization is in decline? Look at the disabled.

The individuals who gave a new language to this old form of ableism were progressives, but they were not the progressives of today. Instead, their beliefs were much more akin to those of our centrist liberals, conservatives, and independents, which explains why they are so durable.

For instance, a coalition of such individuals, many of whom serve in the Massachusetts State House, continue to funnel large amounts of taxpayer money to the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center, a private institution which still uses shock devices on autistic youth nearly a decade-and-a-half after the United Nations cited their methods as a form of torture.

Why? Because the autistic people they shock are deemed to be innately destructive to such a degree that people who like to see themselves as reasonable human beings think violence is a necessary and right response. The problem is, just as they found a century ago, people hold two truths about disabled people in their minds at once. One is that they are potentially dangerous. The other is that they need care.

Time and again, we can see instances where people simultaneously believe in both of these things. When the non-disabled feel even the merest sense of threat from the presence of disabled people it is considered violence. When the non-disabled inflict real violence on the disabled, it is considered care.

The most common argument that sustains the impunity of widespread violence against the disabled is the claim that we are in crisis: that the disabled are overwhelming our systems and our society in unprecedented ways. This allows us to claim that there are no other options but the most draconian.

But the preciousness of believing that we are in an unprecedented moment of disability is almost always debunked by history and in this instance, that history can be found in the hundreds of places like Rotenberg that have existed in this country at one time or another for more than 175 years.

Two crucial pieces of historical evidence emerge from that story. The first is the extent to which the non-disabled have banded together to uphold, rationalize, and enforce the myth of the potentially dangerous disabled person who must be forced to accept help in order to be non-violent: help that often involves forced segregation.

The second is that, generations ago, disabled people recognized that the help they were being told to accept from non-disabled people was just another form of violence, and consequently, some refused to accept it despite the potential for serious consequences.

Where can we see these stories at work in this history? By looking at the instances where disabled people escaped from institutions.

The images in this three-part series explore moments of escape that reveal the ways in which institutions, officials, and community members pursued disabled people who refused to be segregated. It should be understood, as a default, that every single one of these disabled people was escaping abuse of some kind or another. Often this involved extreme sexual, physical, and emotional violence.

Many of these documents are drawn from the archives of the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded, later renamed the Walter E. Fernald State School, which forms the basis of my forthcoming biography of Walter E. Fernald.

A note about redaction: Massachusetts state laws are highly restrictive even when the people named died more than a century ago. Their names and certain identifying information are redacted.

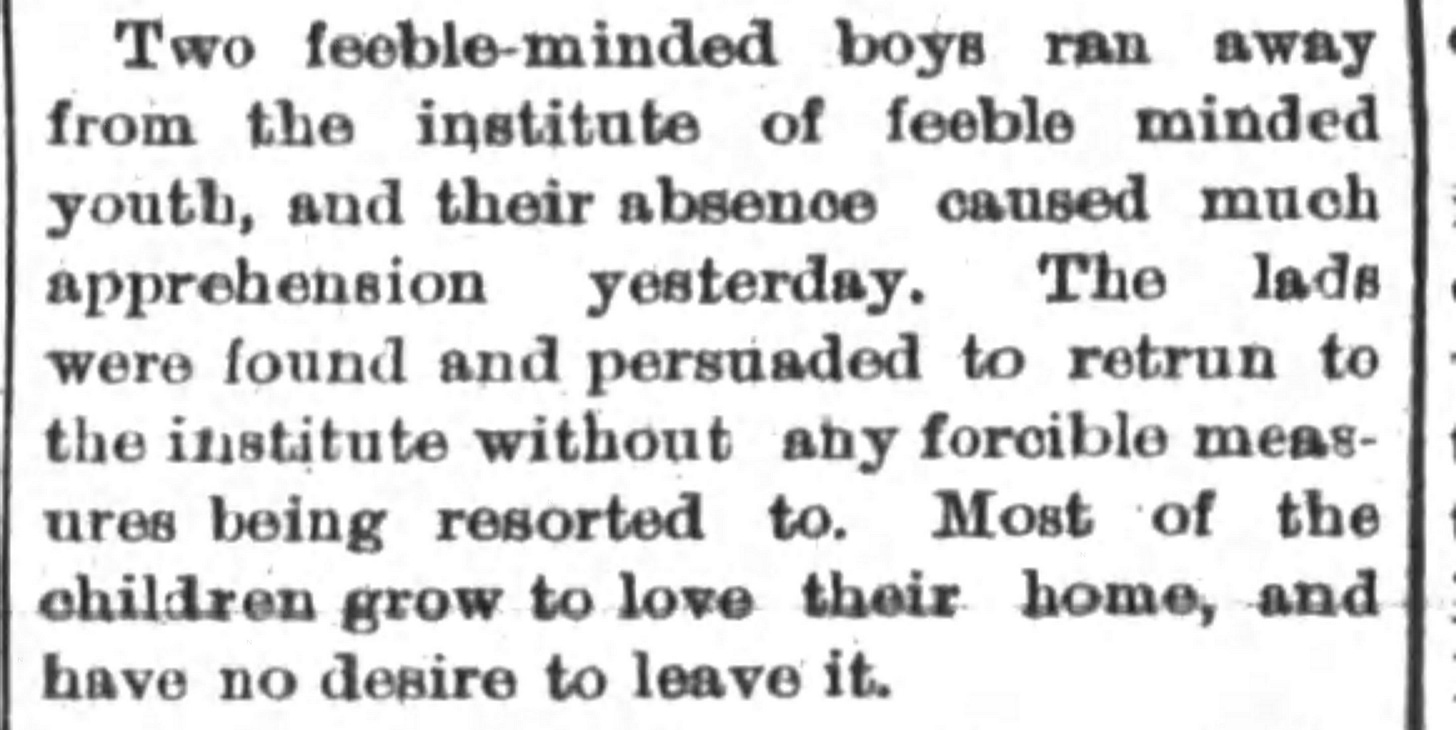

“Most of the children grow to love their home” - 1890

Indiana School for Feeble-Minded Youth

Fort Wayne, Indiana

On July 8, 1890, the Indiana School for the Feeble-Minded opened a mile and a half from downtown Fort Wayne. 300 children were brought from a temporary facility to the new institution, which was intended to act as both a school and a custodial (permanent) institution for the feeble-minded. A little more than a month later two boys from the school put the entire endeavor at risk by fleeing the grounds.

This carefully crafted note, published the next day in the Fort Wayne Sentinel, shows the political balancing act that many institutional superintendents engaged in at that time. Public fears of the feeble-minded meant that the boys’ escape could have easily led to damaging criticism of the institution’s management, especially if it undermined the claims those leaders were making about the effectiveness of the education being offered at their school.

This message told a potentially wary public that children who fled should be returned to the school and that there were ways to capture them without a fight, while gently hinting that force was an option. Perhaps most importantly, by claiming that “most of the children grow to love their home, and have no desire to leave it,” the institution provided the public with reason to distrust any claims to the contrary made by escaped disabled children who might try to plead for help from the people in the community who were being encouraged to run them down.

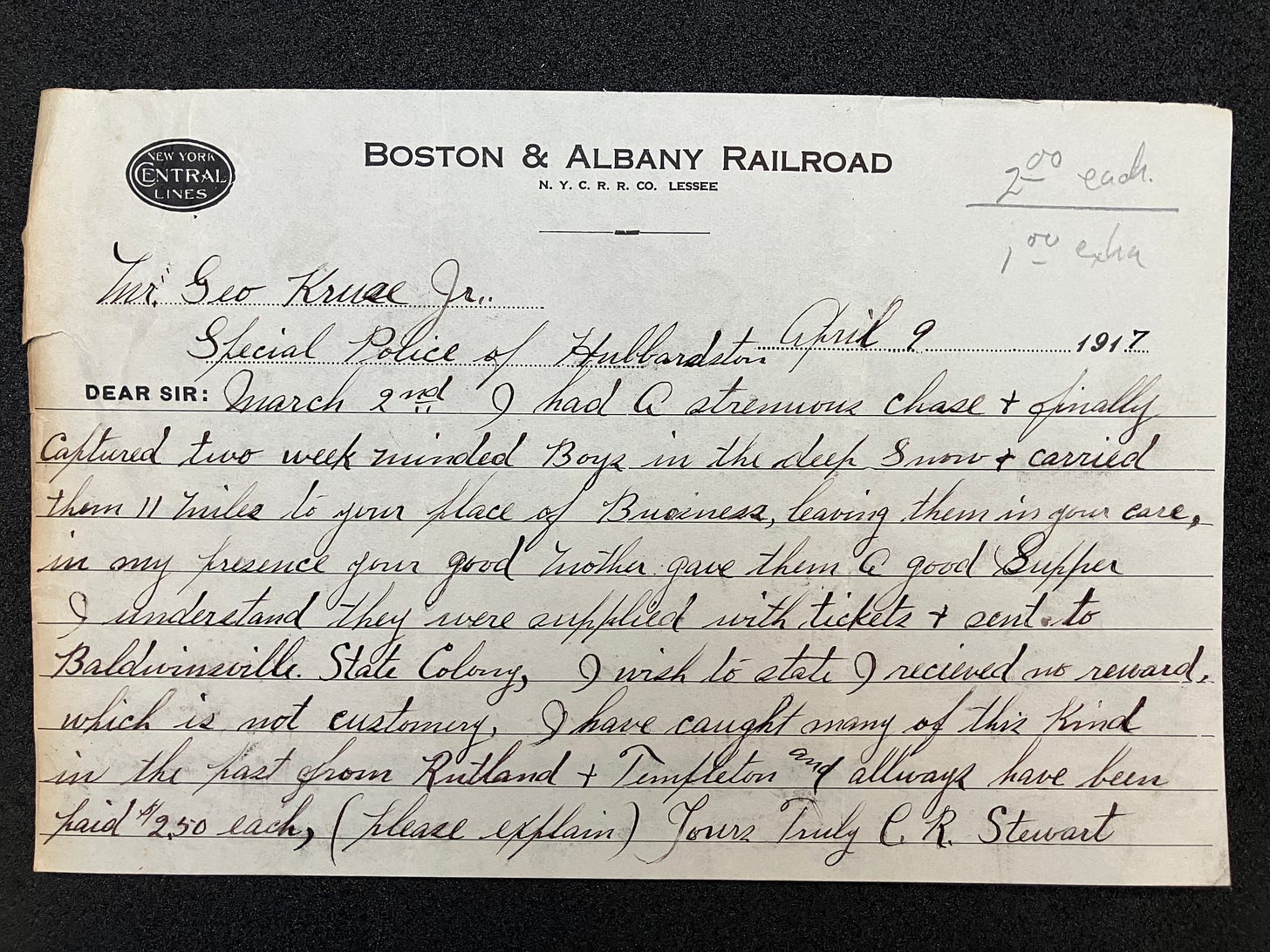

“I have caught many of this kind in the past” (1917)

Templeton Colony of the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded

Templeton, Massachusetts

“I had a strenuous chase + finally captured two weak minded Boys in the deep Snow + carried them 11 miles to your place of Business, leaving them in your care, in my presence your good mother gave them a good Supper. I understand they were supplied with tickets + sent to Baldwinsville State Colony, I wish to state I received no reward, which is not customary. I have caught many of this kind in the past from Rutland + Templeton and always have been paid $2.50 each, (please explain) Yours Truly C.R. Stewart.”

George Kruse, Jr, special police officer of Hubbarston, Mass. forwarded C.R. Stewart’s note to Superintendent Walter E. Fernald. On April 23, 1917, Fernald wrote Kruse, “I want to tell you how grateful we are for your help in returning these boys who had wandered away.” He enclosed a check for $5.00 for Stewart and another of $2.60 for Kruse.

Paying people who make sport of hunting down escapees has a deep history in America. Each situation has been justified in its time for different and haunting reasons. The hunting of escaped formerly enslaved African Americans was justified as a reclamation of property. Bounties on escaped jail and prison inmates were justified as maintenance of public safety.

In this instance, Stewart’s comment about the weak-mindedness of the escapees shows two reasons for hunting down intellectually disabled people who fled. It was at once for their own safety and the safety of others. The potential that something bad might happen to the escapees or others is suggestive, seen as a natural consequence of the inherent risk in their attempt to exist outside of an institution.

It was a lucrative pastime for Stewart. This Macy’s lunch menu from the same year shows the purchasing power of $5.00 at the time.

“Out on Escape” - 1916

Monson State Hospital (Epileptic Hospital)

Palmer, Massachusetts

![Walter E. Fernald, Supt., Mass. School for the Feeble-Minded Waverley, Mass. Feb. 11, 1916. Dear Doctor: I am enclosing herewith photograph of [redacted] a patient out on escape from the Monson State Hospital, and give full description of him as furnished us by the Superintendent of the Hospital. If this patient is committed to your hospital, or anyone answering his description, will you kindly notify Dr. Flood at once, and he will arrange for the patient's return to Monson. “[Name redacted] age 33 years, height 5 feet 1.5 inches, weight 116 pounds; was committed here December 23rd, 1914, as a dangerous epileptic. The only address of correspondent we have is [redacted] Brockton, Mass. I have written the [redacted] but have heard nothing from them. This boy has never been alcoholic. He talks fairly well, has a fair idea of sporting events, knows the name of the Mayor of Boston, the Governor, the President, also of the doctors and attendants here. He does simple math accurately and quickly, is able to work but is very lazy. He has one or two severe fits a month. “The patient secreted his clothing outside of the building and succeeded in borrowing a dollar from another patient. disappeared from this Hospital in the evening just after supper. He would probably go to Boston or to Brockton. I see no reason to suppose that this boy was homicidal, and the reason he was committed here as a dangerous epileptic was largely to avoid calling him insane and yet to obtain legal control. I think he would be a common tramp, and might steal small articles." Very truly yours, Vernon Briggs Secretary Walter E. Fernald, Supt., Mass. School for the Feeble-Minded Waverley, Mass. Feb. 11, 1916. Dear Doctor: I am enclosing herewith photograph of [redacted] a patient out on escape from the Monson State Hospital, and give full description of him as furnished us by the Superintendent of the Hospital. If this patient is committed to your hospital, or anyone answering his description, will you kindly notify Dr. Flood at once, and he will arrange for the patient's return to Monson. “[Name redacted] age 33 years, height 5 feet 1.5 inches, weight 116 pounds; was committed here December 23rd, 1914, as a dangerous epileptic. The only address of correspondent we have is [redacted] Brockton, Mass. I have written the [redacted] but have heard nothing from them. This boy has never been alcoholic. He talks fairly well, has a fair idea of sporting events, knows the name of the Mayor of Boston, the Governor, the President, also of the doctors and attendants here. He does simple math accurately and quickly, is able to work but is very lazy. He has one or two severe fits a month. “The patient secreted his clothing outside of the building and succeeded in borrowing a dollar from another patient. disappeared from this Hospital in the evening just after supper. He would probably go to Boston or to Brockton. I see no reason to suppose that this boy was homicidal, and the reason he was committed here as a dangerous epileptic was largely to avoid calling him insane and yet to obtain legal control. I think he would be a common tramp, and might steal small articles." Very truly yours, Vernon Briggs Secretary](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pxbu!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc86cb102-64fb-4b62-8888-8c9aa0105b1c_2564x3735.jpeg)

The phrase “out on escape” seems peculiar at first, but the description from Monson’s superintendent, Dr. Everett Flood, suggests that the state’s ability to re-commit the man could have faced legal challenges because the man could answer questions that showed his ability to meet a court’s standard for being of sound mind.

Flood was one of the leading figures responsible for propagating the myth that epileptics were dangerous in America and like his colleague in Indiana, he would have known that if he informed the public of the man’s escape, he risked setting off a manhunt and investigation, all of which might end with the man making a successful court claim to be released from custody.

Instead, Flood chose to circulate a letter to his fellow institutional superintendents by way of the board’s L. Vernon Briggs. “Out on escape” was their best semantic attempt to frame an escape as a choice—one that the man might assert if captured—with their own belief that regardless of the legality, they had the right to detain him indefinitely.

Over the coming weeks, this series will continue to explore the historically significant stories of disabled peoples’ escapes from institutions, the collective efforts of the non-disabled to force them back out of society while claiming to offer care, and the importance of understanding this history as the underpinning of our present.