The First Disability Pride Parade: In Their Own Words

As the nation's first disability pride event turns 35, a founder, attendee, and speaker look back

35 years ago, America’s first Disability Pride Day was held just a few miles from where I live, on the streets of downtown Boston. Its story is inseparable from the passage of the landmark 1990 disability civil rights law, the Americans with Disabilities Act, the very same year.

On July 23, Disability Pride will be held again in Boston (details about that here, and below). If you can’t make it, please spread the word that it’s happening, and if you can, you must come. This moment—as you know well from reading the news—demands solidarity between—and with—disabled people.

But if you’re wondering first what disability pride is, and how someone could be proud of their disability, you’re not alone. The organizers and participants of the first Disability Pride wondered and argued about the same things at the time. A few years ago, they shared their reflections with a remarkable group of high school students in my Disability History of America course at Gann Academy, a pluralistic Jewish high school outside of Boston. The interviewees’ reflections are the subject of this week’s (Un)Hidden, but I hope you’ll allow me a bit of reflection before we get there.

A few weeks ago, psychiatrist and writer Elissa Ely penned an op-ed in The Boston Globe about the impact that another Gann student project has had on her—our work in 2018 to uncover the names and tell the stories of every person in the MetFern Cemetery—an institutional burial ground where nearly 300 people were buried under stones marked only with a letter (C for Catholic and P for Protestant) and a number.

In her piece, Ely wrote about reading the students’ biographical sketches and how the imperative, insistent memories they crafted has committed her to a mournful ritual of continued remembrance and memorialization for the once-forgotten lives of the disabled dead. “The facts,” she writes, “are reported with such care, it is as if the researchers wore gloves to cradle the details.”

Rabbi Joshua Gutoff gave us our compass for that work by sharing the words of the great rabbi and philosopher, Maimonides, and we left them up on our classroom whiteboard all year, surrounded by the names of those whose lives consumed our days. “We bury the dead of non-Jews and comfort their mourners and visit their sick because of the ways of peace.”

The facts that Ely described can only be cupped from the ocean of time if the people looking for them are willing to swap the false search for some kind of objective historical truth with a genuine moral trajectory. This means that we must hone our responsibility to uncover history in ways that lead to change and action—what we call meaning—in this world.

The work that goes into (Un)Hidden is essentially about that very idea—replacing the false lens of objectivity with a moral trajectory and the result is that we can see the unseen in history and conjure it in the present. In this moment, where so many of us feel lost about what to do, I know that there is a need to close the loop of this idea of meaning-making by asserting clear visions of the future as well. In the weeks and months to come, where I can make those things out—painful as they may be to hear—I’ll be asserting them more often and more directly.

In honor of that approach, I ask that you share this post about Disability Pride, and if you are nearby, show up at Boston City Hall Plaza on July 23 at noon. March with us. Roll with us. Sing with us. Dance with us. Embrace the radical idea that, amid the very real challenges of being disabled on this planet at this moment, there is also space for the thing called disability pride that our forbears in this work envisioned 35 years ago. I hope you enjoy reading some of their words below.

America’s First Disability Pride Parade

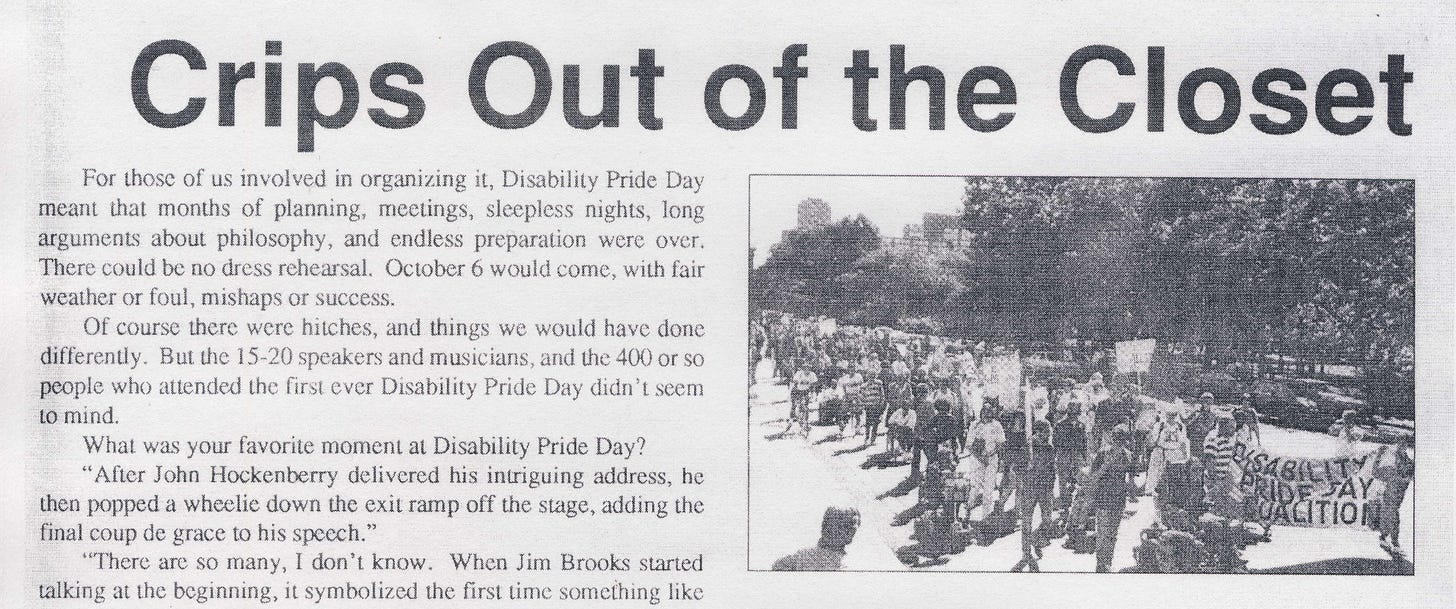

On October 6, 1990, a parade of 400 people started off from Boston’s City Hall Plaza with a Volkswagen Golf rolling alongside them, blaring music onto Tremont Street from a cassette deck. They headed down the hill to Boston Common where more than a dozen speakers and musicians greeted them from a stage in what is widely believed to have been America’s first disability pride parade.

“I think the whole day was really memorable because it was the first time,” an organizer told the publication Roll Call at the time. “I thought that this is something that will go down as a date in history books. They’ll have [celebrations honoring] the Battle of Waterloo and Disability Pride Day.”

“It was when we were marching down Tremont Street and one song came on—I think it was ‘Dancing in the Streets’—and I started dancing around,” another organizer said. “I was on a complete high. Everybody was behind me and in front of me, and the music was high, and I was twirling around out of breath.”

Some quotes below have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Charlie Carr, Disability Civil Rights Leader

“This parade t[ook] place right around the Capitol Crawl [and] all of the work that we had been doing with the Congress to pass the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act]. So people with disabilities were just totally, totally tweaked. We were fired up. We were really, really angry. We were really feeling ignored, on our own, [and] our elected officials wouldn’t listen to what we had to say. [They were] stonewalling passage of the ADA and it was just a really difficult time.

“So I think people with disabilities, at that point in time, were developing a shared identity and feeling like we were all in this struggle together, and we were coming together like never previous to this, meeting talking, sharing.

“And I think there was this moment, and it’s tough to say when, but we felt like it was okay to have a disability. In fact, that was really cool to have a disability. And we wanted to be identified as people with disabilities. And we wanted to feel good about it. In fact, we were prideful and we didn’t feel like we were these stigmatized group of people that should be shut away out of sight and out of mind. In fact we felt like we had power. We had dignity. We had value. We had words. And we were charged with that feeling.”

Amy Hasbrouck, Organizer

“I came to disability rights from the women's rights and other social justice movements, and I think about the comparisons between the way oppression—this monster, Oppression—affects different people.

“One of the similarities in experiences between people with disabilities and gay folks is that—and this relates specifically to my experience as the only disabled person in my family—I knew there was something about me that people didn't like, that people found unpleasant and uncomfortable, and people didn't really like to talk about. I had to hide it as much as possible, and I had to pass as much as possible. I didn't have a lot of support in my family for being who I was.

“I had seen a lot of gay people who had had a similar experience, and that that was one of the things, that was one of the problems that the [LGBTQ] pride movement addressed very well.”

John Hockenberry, Journalist & Main Speaker

“It was a real learning experience for me because I would go to places where people, you know, didn't have a national audience and didn't have a really good job, and who were dealing with all kinds of economic issues as well as health care issues and issues of discrimination. And, I was coming at this from a position where, yeah, I understood what disability discrimination was all about, but I didn't really understand the the nitty gritty of what it meant […] I didn't have that fire in the blood of the advocates and the people who were there on that day.

“And so what was really meaningful for me in going to these experiences, culminating with that parade—which then I think set me off in a fundamentally different direction spiritually—is [the idea] that, you know, we're not just disabled and hanging out, you know, at various places. If we don't figure out how to project solidarity, and be together and understand that our experiences are all related, we don't have a chance. […]

“And so the people who convinced me to be a part of the parade, reminded me that, like, ‘hey, you know, you need to find true religion a little bit, Hockenberry, and we want you to come here to both speak to us, but also to get your eyes opened a little bit.’ And, you know, that was a bit of … it was a really important moment for me.”

A Manifesto for Disability Pride

“Early planning meetings focused more on goals, philosophy and ideas than logistics. There were multiple discussions of the difference between pride in our accomplishments as people with disabilities, versus pride in our disabilities themselves. ‘Are we proud of ourselves despite our disabilities, or because of our disabilities?’ Trying on the latter idea was exciting and even a little scary at the time. There was often heated debate around whether a proposed speaker (such as a vocational rehabilitation commissioner) represented a ‘Disability Pride’ perspective.

“Early on we developed a platform statement to summarize our message for the event:

Disability is a natural part of the human experience.

We take pride in ourselves as people with disabilities. As such, we object to unrealistic media portrayals of persons with disabilities, and the quality of life with a disability.

All people, regardless of limitation, are entitled to the maximum quality of life. This includes food, shelter, clothing, health care, medication and adaptive equipment, transportation, communication, help with activities of daily living, recreation, companionship, and spiritual and personal development, including education and occupation.

Every human being, regardless of limitation, has the right to self-determination.

Each person has the right to maintain and express his/her dignity.

We have a right to maintain our culture, without forced assimilation into the dominant culture.

It is primarily the physical, attitudinal and institutional barriers within this society -- not our disabilities -- which limit us. As we work to eliminate these barriers, so must the non-disabled society here and around the world.

We recognize and embrace the diversity among all people, including within the disability community.

People with disabilities must be given information about, and the opportunity to express our sexuality. We must be granted full reproductive rights and free choice in matters of family planning, including access to information, and techniques -- contraception, fertility assistance abortion and sterilization -- and be free from coercion or force in these matters.

People with disabilities have a right to be free from physical, emotional and sexual abuse.

People with disabilities have a right and duty to participate in the political process. This includes access to information, government activities and meetings, and polling places.

“If I recall correctly, the second statement of the platform ‘we take pride in ourselves as people with disabilities’ represents a compromise position that wasn’t as strong as some members of the committee (namely Jim Brooks and Diana Viets) wanted.”

First published as “Pride Memories” by Amy Hasbrouck in Pride Platform

Members of the Disability Pride Day Coalition Included:

Alan Wein (advocacy director at BCIL), Jim Brooks, Diana Viets, Brian Shea, Cyndi Miller, Karen Schneiderman, Linda Long-Bellil, Carrie Dearborn, Michael Muehe, Bill Donovan, Sybil Feldman, Peter Wong, Mark Limont and Amy Hasbrouck.

![Disability Rights Activists Hold Historic Pride Day [Gay Community News, vol. 18, no. 14, October 14-20, 1990.] In the tradition of the gay pride and Black power movements, the first ever Disability Pride Day was held here Oct. 6 More than 400 people marched, drove, wheeled, and moved from City Hall to Boston Common in a demonstration to affirm that, "far from tragic, disability is a natural part of the human experience,' according to the platform statement by the Disability Pride Day Coalition Disability Rights Activists Hold Historic Pride Day [Gay Community News, vol. 18, no. 14, October 14-20, 1990.] In the tradition of the gay pride and Black power movements, the first ever Disability Pride Day was held here Oct. 6 More than 400 people marched, drove, wheeled, and moved from City Hall to Boston Common in a demonstration to affirm that, "far from tragic, disability is a natural part of the human experience,' according to the platform statement by the Disability Pride Day Coalition](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!FIFP!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0fb73c3f-0972-40bd-a845-2d53b94e6fda_1578x1592.png)