The Haunting Origins of Robert F. Kennedy’s ‘Healing Farms’

America has a long history of enslaving disabled people and calling it treatment

Two notes: A fuller story of Templeton Colony appears in my forthcoming book A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled, which will be published by Bellevue Press on April 1. Apologies that this week’s edition of (Un)Hidden does not contain an audio recording. One will be forthcoming.

The first person I ever heard describe Templeton Colony was a gentle, soft-spoken retired occupational therapist who was sent there by the state at the start of her career in 1982. “It just seemed like such a disconnect from society,” she said, describing the hundreds of disabled men farming the fields in an isolated pocket of rural, north-central Massachusetts. “I heard that originally, the young violent men were attached to plows...to plow the fields,” she added.

Templeton Colony is forgotten today, but its legacy is worth contemplating at a time when there is widespread concern about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s support for “healing farms” as a form of rehabilitative treatment for people who take anything from anti-depressants to those with substance abuse disorder (he considers them one and the same). After all, Templeton is where the world first found a model system for enslaving disabled people on farms and calling it treatment.

The colony began as a utopian ideal akin to the one Kennedy extolled in remarks last June. In 1887, Walter E. Fernald, a young doctor from Maine was given the keys to a squalid residential school on the South Boston waterfront. The Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded was in shambles, but it held pride of place as having first opened in 1848 as the nation’s first public school for intellectually and developmentally disabled children. Fernald swiftly set about fixing the school and established himself as a tireless and brilliant physician endowed with a unique compassion for a group of people who were and are, widely reviled and abused.

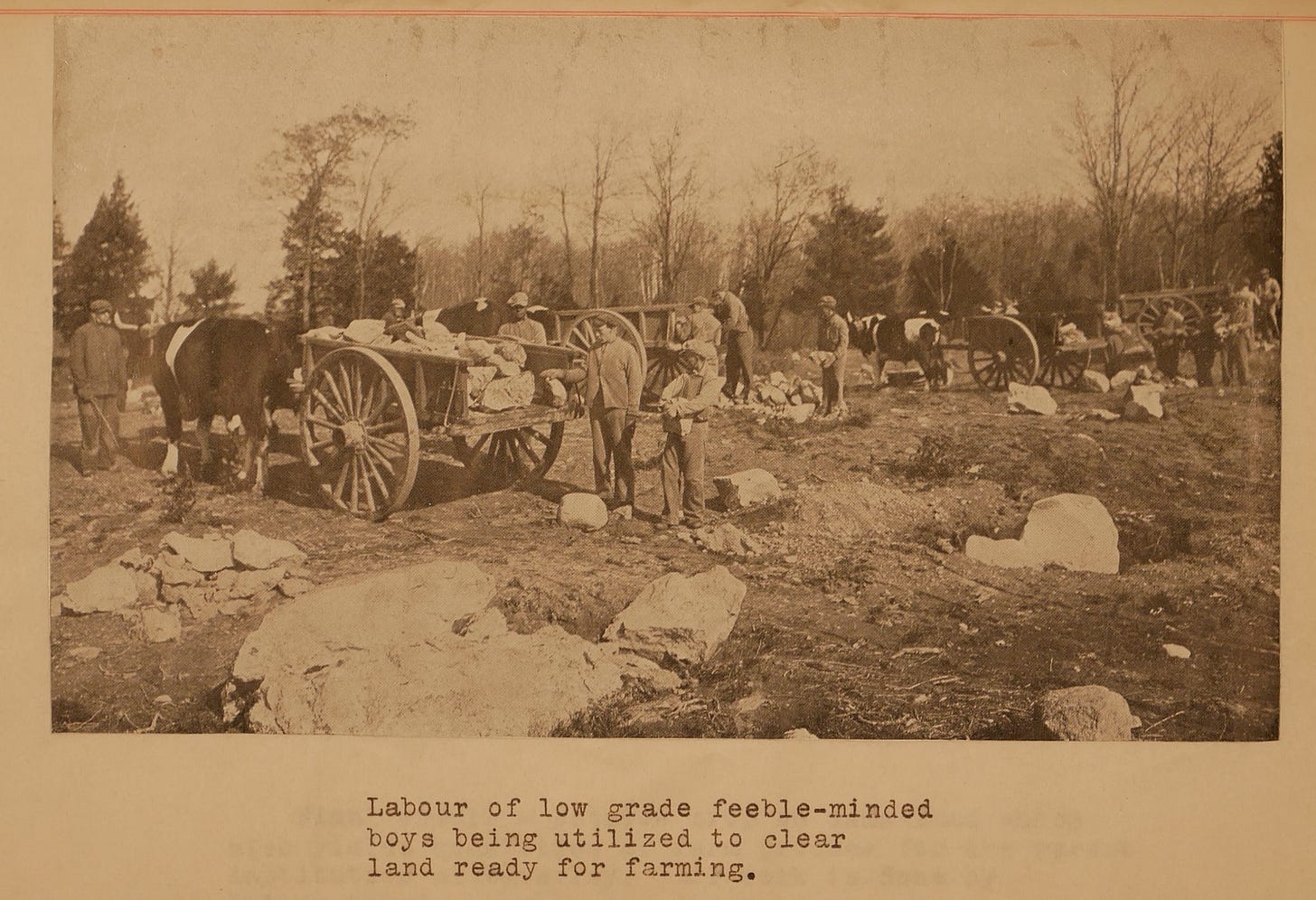

He removed the school to a sprawling slope of farmland 9 miles of west of Boston and steadily expanded it as something of a utopia for disabled children. He was pleased with the school’s success, but was also a tireless tinkerer, and began to worry about certain populations of the school, in particular boys who were growing up and had no one to return to when they finished school. These boys had cleared the rocks, built the foundations, and painted the walls of his new institution but they were getting older, running out of things to do, and space was at a premium.

Fernald soon developed a plan to help them. In 1899, the school purchased 1,600 acres of farmland in Templeton, nearly fifty miles from the new campus. As they grew up, the young men would be sent to the colony instead of the state’s many mill towns, hamlets, and cities. There they would clear and farm the land, supplying the main institution with the food its students needed. It would be rustic and they would learn skills. Over time, Fernald envisioned that they would earn their freedom and be given a plot of Templeton’s land to farm as their own.

Plantations and work farms were not a new idea, nor were farms at mental institutions. Moreover, colonies were all the rage at the time. But Fernald’s power was his capacity for synthesis, perfection, and political persuasion. His colony became the model for farming as an accepted and organized method of “training” the disabled and over subsequent decades it was used at asylums and state schools that eventually housed roughly three-quarters of a million disabled Americans, often for life, in conditions that Robert F. Kennedy Sr. described in 1965 as a “snake pit.” It also worked its way into the policies of other nations, including Britain, whose Royal Commission visited in 1905 and hailed the colony as “extraordinary” before baking the idea into the U.K.’s 1913 Mental Deficiency Act.

Of course, Fernald’s promise of freedom never came true. Within a handful of years, he came to see the place as ungovernably isolated from the main institution and by then, he was in the throes of a decade-long period of pessimism in which he stopped letting all the pupils go and started calling them inmates: a practice that became the norm nationwide. His dark turn was influenced by eugenics, the pseudoscientific belief that humans should control the breeding of other human beings to ensure that only the best traits are passed down, even if it means segregating, sterilizing, and murdering certain (often disabled) people.

But Fernald was not just a follower of eugenics. He was a recognized leader in the movement’s first decade in America and contributed the idea of “defective delinquency,” arguing that one possible expression of so-called mental deficiency was delinquency, which became the underpinning for Henry Goddard’s idea of the moron and continues to shape thinking about addiction, crime, and mental disability today.

Fernald eventually broke with the eugenicists. He did not share their vicious racism and ended up leading the first significant and successful legal challenge against their plans for the forced sterilization of the disabled. He ended his life calling for the undoing of the large institutions he had evangelized for. But all of it was too late and while Fernald’s initial vision for the place may not have seemed like enslavement, there is no way it could have seemed otherwise by the time he was calling for its dismantling.

Nonetheless, Templeton staggered on because others found it, and places like it, to be a convenient way to enslave the disabled and use them to lower the cost of their confinement. The euphemism used to describe the enormous amount of free labor done by the inmates in the 1960s was “the patient mix,” and when reforms came and institutions could no long rely on enslaved inmate labor, they collapsed. Still, the idea lives on in places like San Patrignano, the Italian facility accused of shackling and caging children, which Kennedy sees as a model.

There is no way that Mr. Kennedy could know all of this but he seems like the right kind of person to naturally drift toward these kinds of ideas and to believe that the lesson of history tells him that he can get it right, rather than what a humane person sees immediately, which is the lesson to never do this at all.

His followers see in him a righteous hatred of disability and a rage against the things that cause it, as if it can be reduced to one singular cause and one singular effect. At its best, it comes across as an appropriate disgust with powerful people in society for the disabling effect their pompous decision-making has had on so many vulnerable people. This can seem like a kind of surprising and refreshing class warfare led by a man who has turned his back on the rich and powerful to stand with regular people.

But so often, Kennedy’s entitlement and choice of friends undermines this image. He likes being rich and seen as expert, just as much as he claims to reject the very people who have those same attributes. A recovering addict who is disabled, perhaps he thinks that he could never do something that would hurt disabled people, except that history is riddled with people like him, especially eugenicists, many of whom were and are disabled.

That’s why the way he expresses his outrage about disabilities is so frequently alarming. At his worst, the brutality of what he’s proposing—including the deprivation of disabled rights, forced segregation, and the potential for forced labor—signals a shift from hating the fact that people are disabled to hating disabled people.

It is difficult to know whether he remains as steadfastly committed healing farms as he was last year or if he could succeed in creating them. After all, Mr. Kennedy is a 71-year-old man with few notable accomplishments and a moth-like attraction to the flitting lights of conspiracy and quackery. But in light of this nation’s history, his interest and inclination to pursue so odious and patently awful an idea is rightly cause enough for alarm.