Will Doctors Step Up in Hard Times? History Weighs In.

Doctors side with the powerful, not their patients.

Listen to this week’s episode here, or read on below:

It’s challenging to write a 300-page book. It might be even harder to get that story down to a page or two, but I’ve tried to do it in two pieces this week ahead of the April publication of my book, A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled. [Pre-order from not-Amazon here.] I’ve also been seeing connections between some of the history in the book and today. Below, I’ve shared some rough thoughts below about why doctors are unlikely to band together and do anything to benefit disabled people in these difficult times, and what that means about being good citizens ourselves.

A Harvard Magazine Profile of Walter Fernald

In Harvard Magazine, I wrote about Walter Fernald’s outsized role in shaping major forces we see around us, from his creation of modern special education as we know it to his role as a member of the founding faculty of the Harvard Graduate School of Education. You can read the article here.

“This Man Destroyed a Lot of Lives to Get the Answers He Was Looking For,” An Interview with Publishers Weekly.

At the same time, alongside a stunningly beautiful starred review in Publishers Weekly, I had the chance to chat with Colm Mckenna for a Q&A in the magazine, discussing some of how I first came across Walter Fernald’s untold story. You can read the interview here.

This Week’s (Un)Hidden…

In History, Just as Today, Doctors Rarely Take the Side of Public Health

An unwillingness to confront the powerful is how doctors ended up being complicit in the two most deadly American public health crises of the last half century.

In 1924, the nation’s most prominent child psychiatrist, Dr. Walter Fernald, stood before his colleagues as the president of the American Association for the Study of the Feeble-Minded and told the story of his 30 years of work, much of which was spent building large-scale institutions for intellectually disabled people. He proposed something radical. Institutionalization was largely unnecessary, he said. Institutions should be “decentralized”, and a society built around policing the disabled should be replaced by one where communities were held to account for their treatment of their disabled citizens.

In the present day, as Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. takes the nation’s highest federal health position, Fernald’s is an important story, especially given the widespread and growing exasperation with doctors and medical associations for failing to rise to the moment. But while it would be easy to think of Fernald’s as a powerful tale of boldness and leadership calling us to action a century later, what matters more is what happened next. Fernald returned to Massachusetts, died six months later, and his fellow doctors did absolutely nothing to stop the growth of large-scale institutions nationwide.

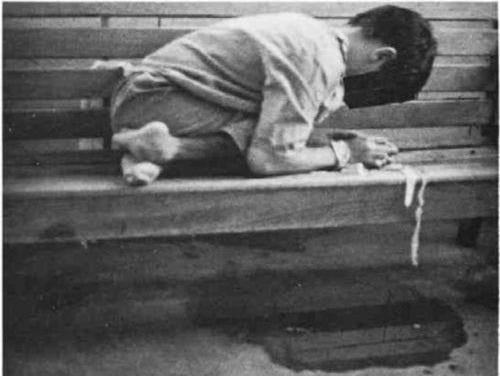

When I spoke with a prominent doctor about his visit to Fernald’s overcrowded institution forty years later in the 1960s (by then it had been perversely re-named the Walter E. Fernald State School), he told me he found himself in a room filled with dozens of naked inmates with Down syndrome, crowded together, covered in feces, totally silent. His first thought, he said, was that doctors were to blame for aligning themselves with the powerful, and urging parents to throw their children into places where they knew that conditions were often something akin to concentration camps.

By that time, decades after Fernald’s death, American institutions for people with mental disabilities were at their peak, with hundreds of gothic asylums and state schools housing well-over half a million people. Ultimately much of that system was dismantled by parents, families, political allies, and the disabled ourselves, though it remains in some form in many places today, including Massachusetts.

For decades, Americans have ingested a different story: one about compassionate and caring doctors who will stop at nothing to save their lives. But it serves no one to treat myths as though they are reality. Your doctor might care about you (though, as Dr. Lisa Iezzoni has rigorously shown, disabled people have reason to feel differently) but that has rarely translated into meaningful proof that doctors collectively care about us.

Instead, time and again history has shown us that doctors are unlikely to do the basic public education we need, and even less likely to take a stand when someone as powerful as they are does something that endangers our public health. With scarce resources for safeguarding ourselves, it would be folly to waste time expecting otherwise.

Indeed, the story of institutions is largely one of medical complicity for personal and professional gain, well after doctors were warned of its failures by their colleague. Aided by doctors in private practice, government-paid physicians built a ghastly system, and because of the power it afforded them, they maintained it at the expense of the disabled, all while claiming that their choices were the neutral and impartial actions of scientific practitioners.

When pushed, they regularly told the public that they were already stretched too far to be able to take a stand. When pushed harder, they talked about reforms, rather than doing what was right, and ending the practice altogether. Their failures meant that many doctors ended up participating in de-institutionalization without truly supporting it, and the result is that doctors were among the first to bring the idea back into popular discourse over the last ten years.

It's a story that can be found time and again on issues ranging from women’s reproductive health to equal access to basic care. But if our moment seems worse than before, it is largely because of the media infrastructure that turns doctors from everyday people into valorized celebrities. With television dramas like Grey’s Anatomy and House as their backdrop, today’s famous doctors have followed a common path of the social media age, by becoming products in and of themselves.

Over the last 25 years a thousand little inactions by the medical community proved to these entertainers that they could amass power without consequence. Mehmet Oz hawked supplements and bogus drugs for years. He now runs our largest health safety net while Scott Atlas, as a presidential emissary, made a thinly veiled proposal for people to use Thanksgiving dinner as a tool to kill off older Americans during the Covid-19 pandemic. In liberal camps it’s no better. Affordable Care Act (ACA) architect Ezekiel Emmanuel proposed the idea that it’s best for everyone if we die at 75 while Yale psychiatrist Bandy Lee was allowed to diagnose a president’s mental state from afar for years without consequence.

This unwillingness to confront the powerful is how doctors ended up being complicit in the two most deadly American public health crises of the last half century. Instead of fighting Big Pharma full throttle, they doled out the pills they were given by reps, setting the baseline for the opioid crisis. When the pandemic arrived, they equivocated on basic, settled facts as simple as masking and frequently ignored the public health needs of disabled people to deadly effect.

These two crises have also exposed a particularly disturbing disconnect between doctors and the rest of us, from disabled people on one end all the way to anti-vaxxers on the other. In a failing system that they have built and they have the most power to influence, they have spent years re-framing instances of mass public death as a story about why they are burned out and cannot go on. These kinds of claims are hardly new, but they tell us through actions what we need to know, which is that the rest of us would be best served by lowering our expectations.

Instead of pointing to single anecdotal examples of good doctors we all know and then expecting them to come together to take a meaningful stand, we have to accept that we have a system where most of them could do something of significance on many fronts—from single-payer health care to a basic public understanding of contagious disease—but will not. That’s a shame, but perhaps we should look to history for how we should act, too. The history of de-institutionalization that began half a century after the death of Walter Fernald holds some answers. The wins disabled people and their allies secured were the result of thinking past doctors with a vision of what they wanted their lives to be, living in non-institutional communities, making daily decisions about how to live.

Their assertion of that vision was powerful enough to drag others, even grudging doctors, along. Without a similarly clear vision today, there is no way to do anything but worry and react to bad news. That is no place to be. So while you fight to preserve the big federal laws that you must fight to preserve, and while you keep an occasional eye on the actions of people like the new Secretary of Health and Human Services, perhaps it’s best to look around where you live today and ask what you can build beyond these things, and what others might already be building around you in plain sight.

A good place to start, always, is with questions. Are the disabled people in your community living full and equal lives? Have you ever asked? Can you help make sure they continue to have that right in deeply meaningful ways that redefine what it means to be a civil society and loving community? Do you need the American Medical Association to support you for that to happen?