How a Student Journalist Freed Thousands of Disabled People from Institutions

Plus an upcoming book talk and coverage in the Washington Post and Boston Globe

Before diving into this week’s piece, I’m thrilled to share some great news about my book, A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled. Today’s Sunday Boston Globe features an interview with me by Walter Fernald’s great-great grandson, and The Washington Post closed out April with A Perfect Turmoil on its list of “11 new paperbacks to read this month.”

I hope you’ll join me for a reading and conversation on May 15 at 7 p.m. Belmont Books with New York Times bestselling novelist Laura Zigman, who has her own personal ties to Walter Fernald’s institution.

Listen to this week’s edition here or keep reading for more (note, due to length, some of this email may need to be read at unhidden.substack.com):

(Un)Hidden is about seeing the unseen. To that end, I apologize in advance for a somewhat longer edition of (Un)Hidden: Disability Histories and Our World this week (and some stumbling words on the recording above), but I wanted to share a remarkable, previously unseen piece by a student journalist—James Frieden—who managed to get inside the locked-off parts of the Fernald School in 1971, and used what he saw to free thousands of disabled people from institutions.

I found Frieden’s article in a box in an abandoned building, underneath a desk. No other copy of what you’re about to read exists.

Most striking to me is the Frieden’s mention of institutional employees’ faking of death certificate information to mask the true cause of death of a disabled inmate. For historians, a single piece of information like this has signficiant implications, and it did back in 1971 as you’ll see below.

It’s also a reminder that journalism has an essential place in our moment in time. Given our political conditions, disabled people will almost certainly face increasing levels of abuse and there will be less accountability for it. That is, unless we have other means of exposing it. There was a time when student journalists were at the forefront of that work and we will need them again.

A Journalist-Turned-Disability Advocate

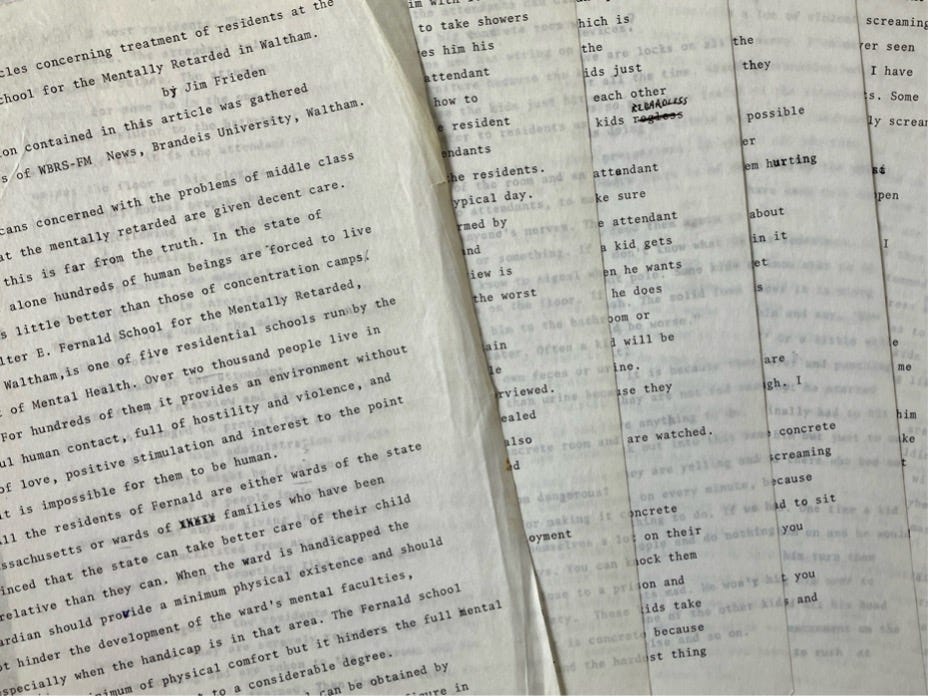

In 1971, a two-part series aired on Brandeis University’s student radio station, WBRS, describing the conditions inside the Walter E. Fernald State School, the nation’s oldest public institution for intellectually and developmentally disabled people. Today, all that survives from those programs is a typescript transcript of the first segment, but even in its partial state, it reflects the exceptional journalistic skill of its author, James Frieden, who was then an undergraduate at the university.

Frieden had been granted unrestricted access to the 2,500-inmate1 Massachusetts institution and was guided through it by attendants who were eager to expose the cycle of dehumanizing rituals that characterized life there. Intellectually and developmentally disabled people of all ages were locked in large concrete rooms for hours each day, often naked and covered in feces. Those who had arrived knowing how to use a bathroom soon forgot. Extreme injuries were common. Inmates were drugged and beaten. Deaths were covered up. When one inmate choked to death during a forced feeding, his family was told he died from pneumonia.

“Most Americans concerned with the problems of middle class life assume that the mentally retarded are given decent care,” Frieden said that the time. “Unfortunately this is far from the truth. In the state of Massachusetts alone hundreds of human beings are forced to live in conditions little better than those of concentration camps.”

Frieden was only partly correct. By 1971, many Americans were aware of institutional conditions but chose to ignore them, beginning with Life magazine’s publication of “Bedlam, 1946,” a two-part photographic expose of institutions in Pennsylvania and Ohio. In the intervening years, parents had organized for the rights of their disabled children, disabled people were increasingly advocating for themselves, and President John F. Kennedy had given their efforts his blessing with landmark 1963 legislation intended to move toward a model of community behavioral health and away from mass institutionalization.

Throughout the 1960s, a steady drumbeat of reporting documented the fact that, if anything, conditions in institutions were getting worse. Just months after Frieden aired his reports from Fernald, one of the most explosive pieces in American history would hit televisions nationwide when Geraldo Rivera documented the squalor at New York’s Willowbrook State School. But by then it was clear that even growing public outrage would not be enough to transform and then shutter institutions.

America’s laws—which had almost solely been used up to this point to punish disabled people—now needed to be redrawn to affirm that they had the same fundamental rights as anyone else. Unbeknownst to Frieden, he was about to find himself among a vanguard of people who understood that fact and were taking the rights of the disabled into America’s courts.

Soon after he graduated, Frieden received a call from Gunnar Dybwad, a Brandeis professor who had emerged as the leading voice for legal protections for intellectually and developmentally disabled people in America and abroad. Dybwad was part of a group of lawyers pursuing a novel strategy in Pennsylvania, suing the state’s Pennhurst institution for segregating disabled children in violation of the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling on racial segregation in Brown v. Board of Education.

Dybwad had heard Frieden’s reports on Fernald and urged him to take a job working for state representative Alexander Lolas who was a member of a Massachusetts commission investigating death rates at the Belchertown State School and Monson State Hospital; state institutions located in Western Massachusetts that were similar to the Fernald School.

Frieden took Dybwad’s advice and soon came on board, serving as Lolas’s aide on the commission. There, he was joined by a large number of doctors and a handful of prominent advocates for the disabled, including the commission’s lawyer, a former state senator named Beryl Cohen.

From the outset, Frieden found the work was as difficult as it was rewarding. Deaths in the state’s institutions were significantly higher than the general population. The commission came to believe that the high death rates were caused by the fact that doctors in state institutions did not have to be accredited to practice in the United States. After conducting the review, the state took up the commission’s recommendation to provide institutions with funds to recruit local doctors when there were emergencies, which brought about a substantial reduction in the number of institutional deaths.

Given what he had seen, Frieden felt that more significant changes were needed, but it was clear to him that the doctors on the commission were not willing to do much more. Then one evening, he was watching Walter Cronkite, the nation’s leading broadcast news journalist, and heard something that caught his attention.

“[Cronkite] gave a report on the first right to treatment case ever filed in the United States,” Frieden told me in an interview earlier this year. “The theory of the case was that since inmates of mental institutions were confined against their will without having been convicted of a crime, their confinement could only be justified if they were receiving treatment. However, if they were simply warehoused, like the mentally disabled residents of the state schools in Massachusetts—and all over the country—their imprisonment was without due process of law and illegal.”

Filed in Alabama, the case was called Wyatt v. Stickney, (incidentally, Gunnar Dybwad had been an expert witness in the case), and Frieden immediately understood its potential importance for the Massachusetts state schools. The next day he rushed to the commission’s offices and told the lawyer, Beryl Cohen, what he had heard.

“I suggested…[that we] file a class-action lawsuit on behalf of all the residents of the Belchertown State School alleging that the residents were being imprisoned without trial and conviction of a crime but were not receiving any treatment,” Frieden later recalled. “This would be a way of forcing the state to spend more money to upgrade conditions of the state schools.”

He proposed that they ask another member of the commission, UMass Amherst professor Ben Ricci, whose son was an inmate of the Belchertown State School, if he would lead a class action lawsuit as his son’s representative. It took three tries for Frieden to persuade Cohen, but in February 1972, a year after Frieden’s pieces on the Fernald School aired at Brandeis, Beryl Cohen filed Ricci v. Okin in Massachusetts federal court, alleging that his son’s fourteenth amendment rights were being denied. Filed weeks before Alabama extended the Wyatt ruling to intellectually and developmentally disabled people, it was a landmark suit.

The case was handed to a newly appointed federal judge named Joseph Tauro. Tauro’s unannounced visits to institutions and his visceral denunciations of their conditions impelled state leaders to enter into long-term judicial agreements called consent decrees, where the judge could demand sweeping reforms and large-scale spending to improve institutional conditions. In the earliest days of the lawsuit, Frieden found himself alongside Cohen in negotiations with Tauro, fighting for details that would finally bring about an end to some of the worst abuses in Massachusetts institutions.

Over time, the Ricci lawsuit was joined by groups from every state school in Massachusetts and in 1978 Governor Michael Dukakis agreed to enter into the consent decree. Governors around the country soon faced lawsuits of their own based on the rulings in Alabama, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. Time and again, they discovered that it was financially impossible to maintain large-scale institutions in ways that respected the equal rights of the individual. In the 1999 Olmstead ruling, the Supreme Court effectively determined that large-scale institutionalization was unconstitutional. In Massachusetts, thousands of intellectually and developmentally disabled people were released because of the Ricci suit, and today only two moderately-sized state run facilities of their kind remain open.

Unsurprisingly, after his work to launch the Ricci lawsuit, Frieden went on to obtain a law degree and in the decades since, he has practiced trial law in Massachusetts and Los Angeles, and moved into a new area of work: animal rights advocacy. Along the way, he and his wife also created Teach with Movies, a non-profit dedicated to helping educators teach students about history using films.

You can read the entire transcript of James Frieden’s article on the Fernald School below. It is a harrowing account and near the end, Frieden noted that the legislature, and by extension the people of the Commonwealth, would ultimately have to make the choice about whether they would spend money to end the conditions at places like the Fernald School. “The money is there,” he wrote. “We are a wealthy nation and Massachusetts a wealthy state. It is a question of priorities.”

In a 2018 interview with me and my students, Michael Dukakis was unequivocal about the fact that during his time as governor, the legislature never made it a priority to approve spending that would improve institutional conditions. Instead, they were forced to do it under judicial order. In an era where there are rising calls to reopen large-scale institutions, given all that we now know that compels us not to do it, this is a frightening and cautionary note about the capacity for human beings to neglect the suffering of others, even when they possess all the power in the world to put an end to it.

TRANSCRIPT OF JAMES FRIEDEN’S 1971 WBRS PIECE

One of two articles concerning treatment of residents at the Walter E. Fernald School for the Mentally Retarded in Waltham.

By Jim Frieden

The information contained in this article was gathered under the auspices of WBRS-FM News, Brandeis University, Waltham.

Most Americans concerned with the problems of middle class life assume that the mentally-retarded are given decent care. Unfortunately this is far from the truth. In the state of Massachusetts alone hundreds of human beings are forced to live in conditions little better than those of concentration camps.

The Walter E. Fernald School for the Mentally Retarded, located in Waltham, is one of five residential schools run by the Department of Mental Health. Over two thousand people live in Fernald. For hundreds of them it provides an environment without meaningful human contact, full of hostility and violence, and devoid of love, positive stimulation and interest to the point where it is impossible for them to be human.

All the residents of Fernald are either wards of the state of Massachusetts or wards of families who have been convinced that the state can take better care of their child or relative than they can. When the ward is handicapped the guardian should provide a minimum physical existence and should not hinder the development of the ward's mental faculties, especially when the handicap is in that area. The Fernald school provides a minimum of physical comfort but it hinders the full mental development of the resident to a considerable degree.

The most intimate view of the school can be obtained by talking to the attendants. The attendant is the main figure in the life of most residents. The attendant provides him with food; some he feeds. The attendant tells the resident when to take showers and some, he bathes. The attendant is the one who gives him his clothes; for some he is the one who dresses him. The attendant takes the resident to the bathroom if he doesn't know how to go himself and it is the attendant who cleans up if the resident messes the floor or his clothes. In many wards the attendants are the only normal people who see the daily lives of the residents.

The following is an attendant's description of a typical day. It is quite shocking. Everything he said has been confirmed by other attendants, the administration, or my own first hand observations. It is interesting to note that this interview is about a building which the administration admits is not the worst in the school.

The name of the attendant must be withheld, and certain parts of this interview and any other quotes in the article have been changed to protect the jobs of the people I interviewed. I was told by a high administration official that if I revealed names, the people might be fired on a technicality. I was also told by a number of people including a nationally recognized authority that anyone giving information would be fired and informally blacklisted from any state job in Massachusetts. All they do is put something like " unreliable " on the employment record.

"The ages of the residents in my ward are from ten to twenty-five. They are severely retarded. They get up at seven in the morning and are taken to the bathroom and fed. Most of them are not toilet trained. Then they are taken to breakfast. Meals are just a messy affair. The attendant will shove some food down their throats, get them fed in about ten minutes and shove them out the door so that the attendants can clean up the kitchen. Then they are put in this big concrete room- which is painted depressing greys and greens and has wiring on the windows. There is little or no furniture because the kids just break the furniture. No toys because the kids just hit each other with the toys. (Most attendants refer to residents as kids regardless of their age.)

"So they sit down on the floor of the room and an attendant will stay there with them, maybe two attendants, to make sure they all sit down and don't get on anyone's nerves. The attendant probably wants to read the newspaper or something. If a kid gets up you yell at him. If a kid doesn't know to signal when he wants to go to the bathroom he usually goes on the floor. If he does that you yell at him, and either send him to the bathroom or just leave him there and clean it up later. Often a kid will be ignored and spend hours sitting in his own feces or urine. Feces are more likely to be cleaned up than urine because they smell more.

"After breakfast they sit in the concrete room and are watched. They do this until lunch time."

Question: Isn't an all concrete room dangerous?

"You can't knock the institution for making it concrete because of safety. These kids can hurt themselves a lot on their own. They hurt themselves in a million ways. You can knock them for making it concrete because it is so close to a prison and so cold and inhuman but not because of safety. These kids take care of themselves very poorly. I'm sure it is concrete because concrete is the easiest thing to clean up and the hardest thing to break.

Question: Are there any safety devices?

"The only safety devices they have are locks on all the doors. All the doors are locked almost all the time. Also they have wire and netting over the windows so the glass isn't broken. But basicly [sic] when you have kids. doing as little as possible you don't need to take as many safety precautions. In other words the less the kids do the less chance there is of them hurting themselves.

"At lunch time they take them in feed them again in about ten minutes. The food is like mush. I don't' know what is in it but I wouldn't touch it with a ten foot pole. Some kids get solid food. Some kids can only eat mush. The solid food is terrible institutional food...It could be worse."

Question: Do the kids react to it?

"If they react to it in any way it is because they are hungry. I don't think it is because they are not fed enough. I think it is just that they do not have anything to do.

"After lunch they are taken back out into that same concrete room. 'While they are sitting there they are yelling and screaming and hitting each other. Violence goes on every minute, because they are all packed together with nothing to do. If we had to sit in a bare room with a lot of other people and do nothing you or I would become very violent too.

"If you yell at a kid and he gets mad, he won't hit you because you are stronger; he'll hit one of the other kids and then the other kid will hit someone else and so on.

"Even the attendants get violent. A lot of it is due to the situation. After being in a room with a lot of violent screaming kids for eight and a half hours you get nervy. I've never seen attandants [sic] actually hit kids without provocation but I have seen very violent behavior on the part of the attendants. Some of them are very hostile towards the kids. They constantly scream and yell at them for no reason. They do it all the time. They don’t take the kid somewhere they grab him by the wrist and pull him faster than he can walk. I have seen this happen an awful lot of times.

"It is really hard not to hit residents sometimes. If I hit one it is because I get so mad I don't know what to do when a patient is doing something and he knows it is wrong. If he is hitting someone else I might hit him and say, 'How does it feel? Do you like the way it feels? Or a little while ago one of the brighter kids kept on coming over and punching me which is O.K. He was sort of fooling around but he started getting violent and hitting me hard and I finally had to hit him with my fist. Not nearly hard enough to hurt him but just to make him quit. I don't think anyone has ever worked there who has not hit a kid.

"A lot of violence is caused by accidents. One time a kid was turning light switches off. I would turn them on and he would turn them off. I was bringing him over to have him turn them on again. He wouldn't come so I started pulling him over to the light switch and he slipped on some urine and hit his head against the wall. There is always some urine or excrement on the floor. A lot of accidents occur because you have to rush at certain times like shower and dinner time.

"After lunch, at about 2:30 or 3:30 the afternoon shift comes in. During this time some laundry comes in and is sorted. The kids are kept the same way the afternoon shift found them: sitting down in the concrete room. They do this until supper time. At about 5:00 they take them in, feed them the same kind of supper in ten minutes, get them out again and clean up.

"All day by the way the kids may or may not have clothes on. It depends. You may keep clothes on them or you may just forget about it. What clothes they do have are pretty sad. A lot of them are donated. A lot of the clothes are institutional clothes which are more like straight jackets than articles of clothing. They are all one piece and are buttoned [sic] up the back.

This means that a kid will never be able to dress himself and before he can go to the bathroom an attendant has to unbutton his clothes. They have special clothes for the kids to wear when someone comes to visit them. They are not anything like what they usually wear if they wear anything at all.

“Their day ends with showers. Sometimes there are shower stalls. Soon they will have them in most of the buildings. In some buildings there is just a porcelain table and a hose with warm water. You wash the kid off on each side and maybe dry him off a bit and put some clothes on him. It is done on a mass assembly line basis and there is a lot of depersonalization.

“Most of the operations concerning the kids are depersonalized. There are so many kids to take care of at the same time that you start forgetting the individual kid and only think about what you have to get done. In other words you start thinking to yourself, 'Well, I have really got to these showers over with. You don't think to yourself, 'Well I have really got to get Johnny Jones washed. I have got to wash him off, dry him off and get him dressed.' You think, 'We have really got to get these showers over with,’ and make an assembly line out of it. It happens even if you don't want it to.

"At about 8:30 you give them their medication. Some of them get penicillin or other drugs. A lot of them are physically ill as well as mentally retarded. The medication is often given out by an untrained attendant. This is illegal. If this were going on in a private institution I am sure that there would be a lot of legal trouble. But this is a state institution so anything goes." (I might interject here that the report of The President's Committee [sic] on Mental Retardation MR68 says that many practices in state institutions would not be tolerated in private ones.)

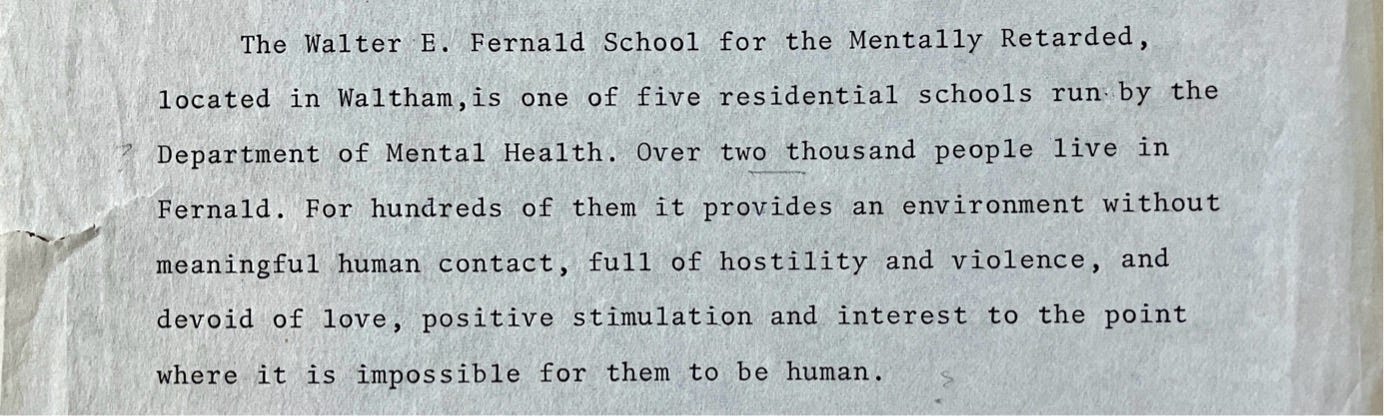

"At night every single one of them is given sleeping pills, chlorolhydrate. If any of them get out of bed during the night they are immediately tied in with a rope. The main thing with custodial care is to make the kids the least possible trouble for the attendants. No procedure [sic] is gone through to determine if the kids need sleeping pills. It is simply standard practice instituted by the night attendants just so the kids won't bother them at night. I was talking with a friend who is in a building that has a federal project in it. He said that when the project began all the kids in his ward were given sleeping pills but that they have stopped giving them and now they are used infrequently and no one, including the worst behaviour problems, needs them regularly. It is simply a practice instituted by the night attendants to save them trouble.

This is the day to day existence of the Fernald residents of one particular building. There are other buildings where the routine is basicly [sic] the same. The damage that this causes is incalculable. Intelligence drops, physical health is impaired and whatever means the person had developed for relating to people atrophies. There are two prevalent responses to this type of treatment. The kids can become either violent or withdrawn. When I toured the school I saw a room with forty or fifty naked screaming men in it. Their ages looked to be from 15 to 50. They were wandering or sitting down. They had raw sores on their bodies and excrement was all over the place. I also saw what looked to be teen-age boys lying naked in fetal positions. Some of them were just lying still, some were rocking back and forth. I understand from my interviews that this is common and can go on all day.

For many residents of a state institution there are no programs for education or creation. Sometimes, if an attendant feels like it, they may get to go out and play on the swings and use some of the other recreational facilities at the school. But this is strictly at the discretion of the attendants. There is no official policy concerning recreation which means that it is seldom done. The residents can swim and can use the swings. They learn to use almost anything they are given. The problem is that they are given very little.

The educational and recreational programs that do exist are often inadequate. The residents who have them may go to school for a couple of hours a day. But this is only a couple of hours for severely retarded people compared to seven or eight hours for normal people who need less intensive instruction.

Aside from seeing a physician there is little professional help for hundreds of people who need it. In every instance that I have come across there have been no psychiatrists or psychologists to help residents on an individual basis even though they may have been diagnosed as probably psychotic on admission. There is the unbelievable case of a girl whose psychotic symptoms were so gross that medical doctors could see them. She could be extremely hostile. They repeatedly recommended that she be transfered [sic] to a mental institution. This went on for a period of years until she attacked an attendant and paralyzed her for life. Finally, she was transferred. There are also no social workers, no physical therapists and no occupational therapists for hundreds of residents. The Newton public school system, which deals with normal kids, is said to provide more individual professional care than Fernald whose residents are abnormal.

The attendants may be the only normal people the residents have much contact with, but it is more than that. The attendants are power figures for the residents. They give them food and what other physical comforts they get. They are the only consistent source of stimuli for the residents and they are the only source of affection if any affection is given. The attendant has been described as a parent figure, an authority figure, and a stimulus-response figure for the residents. The attendants are the only people around who can fill the human need for such a figure. Many residents never see their families. Some see their families a few times a year and a few see them on the weekends.

The care the attendants provide is inadequate to meet the demands of this role. Most of this is not the attendants’ fault. Understaffing is terrible. Even in buildings where there are extra attendants because of a Federal research grant twelve, eighteen, or even twenty-five retarded people are left in the care of one attendant for hours or even whole shifts. (There is a large grant from the Federal government for research in methods of behaviour modification among the mentally retarded.) There is no way for one prson to handle twelve let alone twenty-five mentally retarded people. Their mental age may be 6 or 7 and usually they have behaviour problems. The maximum number the attendants I spoke with felt they could give enough love and stimulation for adequate development was three or four. Time and again they described the impossibility of dealing with large numbers of residents in a humane manner. A mentally retarded person can throw a temper tantrum all day not just for 20 to 30 minutes. If you don't have an isolation room to lock him up in this means that the rest of the residents in the ward will be upset all day and you can't calm them down because you have to spend most of your time with the resident who is throwing the tantrum. If two people act up at the same time and you are there alone it is impossible to deal with both of them not to mention spending enough time with the other residents. Or if one resident is poorly toilet trained and has diarrhea you have to follow him around cleaning up after him all day and you don't have enough time to spend with the rest of the ward. If you are alone your plans can be upset by the slightest thing. Plans seem to be upset often.

Stimulation and attention are of the greatest importance. There was a ward with around fifteen severely retarded residents none of whom were toilet trained. Two new and untrained attendants were hired under the Federal grant. One of their projects was to toilet train the ward. Two or three of the residents remembered toilet training they had previously had and became toilet trained immediately. They had forgotten or just stopped going to the bathroom but once someone started paying attention to them and giving them affection and reward for doing it they remembered. It is equally amazing that within a month half the ward had made substantial progress. When attention and stimuli are denied a mentally retarded person regression usually occurs. In one case a girl who for months had been extremely fastidious regressed markedly. She would take showers and change clothes on her own initiative. She would use her deodorant herself and take pride in her appearance. The attention of the attendants became diverted to something else and this girl stopped taking showers and even lost her toilet training. The attendants feel that it was the lack of attention and stimulation that caused this. It is lack of affection, attention and stimulation that more than anything else has led people to sit on benches for twenty, thirty, up to forty years.

It is in the wards where an attempt is made to instruct and help the patients that the importance of interest and affection is best demonstrated. One part of the research grant I spoke of before seeks to find out how well mentally retarded people respond if they are rewarded every time they do something correctly. It is extremely difficult to teach the mentally retarded anything that is new. Even the simplest thing must be repeated constantly for extended periods of time. If you ever flag the mental retard may forget and you will be set back weeks. An attendant described the situation using one of the boys in his ward as an example. "This boy drags a blanket around and holds it in his hand all the time. Now he is not going to let go of that blanket because it means a lot to him. If you follow him around all day and when he doesn't have the blanket in his hand for one minute reward him with candy the candy will begin to mean a lot more to him than the blanket. But once you aren't there for five minutes, say you are outside getting dinner or in the bathroom cleaning something up, if that kid is good and isn't holding the blanket in his hand and you are not there to reward him the whole thing is completely knocked off. They don't remember well. New behaviour has to be totally and completely reinforced." This is a building where there are often over twenty residents per attendant and regularly twelve or eighteen to one attendant. During the weekends and at night even fewer attendants are in this building.

Nights and weekends the understaffing is the worst. Any new behaviour that might have been learned during the week is dulled or lost. In one building where there are extra attendants from the federal grant there are two or three attendants for well over a hundred residents. In other buildings they used to drug the residents from Friday night to Monday morning because there were so few attendants. There have been instances when more mildly retarded people have been sent in to more severely retarded wards to take the place of attendants.

Many of the attendants are given inadequate training. The administration told me that every single attendant recieved [sic] ten weeks of inservice training. I found, however, that only ten percent of the attendants I interviewed had been given it. I doubt that they are a representative sample but there are well over twenty attentands [sic] who were simply hired and then put on the wards. They were not told how to handle epileptic seizures even though many of the residents in their wards are epileptic. The course when it is given is inadequate and shows the bias of the school. It is mainly training in first aid. No one mentioned any training in how to provide for the psychological needs of the residents.

In addition to shortages of attendants, lack of professional help, and lack of training, inadequacies the institution is directly responsible for, the behaviour of the attendants themselves often criples [sic] their ability to fulfill the role of authority figure. Some attendants are constantly and unreasonably hostile. Many of them are simply not on the wards when they are supposed to be. This further aggravates the shortage of personnel. It can get to the point where the coffee break and lunch hour comprise four hours of an eight hour shift. The attendants in general are resistant to change. Either they don't understand or they think it will make their jobs harder.

The quality of the attendants leaves much to be desired. An attendant makes $105.00 a week. An unskilled construction worker in Boston makes almost twice that. Most of the male attendants are people who cannot get jobs anywhere else. Some of the attendants have not completed high school. The worst example is that of the Haitian immigrants. Some of them can not speak English yet they are employed in a situation where it is important to repeat words so that the residents can learn how to speak.

This is not to say that all attendants are not fit for their jobs. I have heard reports of attendants taking the initiative in training residents and providing them with a modicum of individual care. But usually the attendants give little or no stimulation. It is much quicker and easier to shove food down a resident's throat, push them into shower or lay them on a slab hose one side and then the other than it is to laboriously, day after day, climb into the shower and try to teach them how to wash themselves.

It is easy but it is callous and to my mind criminal. Also it is only human. It is easy to see how an attendant can become hardened. Most of them are hired as custodial workers in the tradition of hiring farm hands. They are hired to feed and provide the minimal physical wants of the "herd". When they get on the job they find that this "herd" consists of human beings. Under the conditions there are only two possible responses: to treat the residents like animals as they are expected to do or to leave and find another job. If an attendant tries to treat the residants [sic] humanely he comes up against a blank wall. There are too many residents to take care of. The attendant has no relevant training and little or no access to professional help. Other attendants resist any attempt at change. They have become inured to treating the patients like animals and don't want their routines interrupted or their jobs made more difficult. There are insufficient materials like games, showers and clothes. Soon the ambitious humane attendant will feel very frustrated and either become hard like the other attendants or leave for his own mental health. It is a basic human reaction. It means that most of the attendants who remain treat the residents very poorly.

Recently there has been a little improvement. There seems to be a group of psychologists headed by the assistant superintendant [sic] who have been pushing very hard for change. They have gotten grants under which they have been hiring a lot of new people in their twenties, given them a 3 or 4 hour training session in teaching methods and provided them with professional guidance, encouragement and more facilities. Unfortunately one of the major grants runs out in less than a year and if the state doesn't start paying for it hundreds of residents will be put back into custodial wards.

Even with the federal grants there are many buildings where attendants are scarce. Where there should be one attendant on duty for every three of four patients there is sometimes a ratio of one to over twenty. Even with the grants there is not enough personalized care.

I find it impossible to express what I know of the misery these conditions create. And I am sure that I haven't seen it all. I can say that the I.Q. level usually drops after a person is admitted, that social skills are lost and that emotional problems are exacerbated. It is obvious that if a resident spends years or decades sitting on a bench he will forget how to do things. But as one attendant said the I.Q. tests don't measure what happens to that person's ability to relate to other people, to feel and to love. It strikes me that those years on the bench themselves are lost. I wonder how many human years have been lost at this school.

The physical plant is bad in itself and reinforces the impersonal and dehumanizing treatment of the patients. The diet is adequate. It is bad institutional food, low on vegetables especially green vegetables, and very very high on starches. The methods of feeding may be impersonal, resemble assembly lines and be ineffective. “When a kid can't feed himself or even if he can he really doesn't know what he is doing it is hard to tell when he has had enough to eat. You don't want a kid to vomit because you are shoving food down his throat but then again you want to see that he gets fed. Also, the attendants are never sure of which kids are supposed to get mush and which kids are allowed to eat solid food. An attendant who works in another building told me that a few months ago a kid who was supposed [sic] to get mush cholked [sic] to death because he was given solid food. The attendant said that his family was told he died of pneumonia."

The medical care is spotty. A doctor comes to each building everyday [sic] and looks at the residents the attendants bring to him. If [sic] a resident complains the attendant will take him to the doctor. In some buildings the doctor does not go around the ward to look at the residents. Neither a hurried attendant nor a retarded person can be expected to notice oncoming diseases and conditions which may become dangerous if not found early.

Medication is often given out by untrained persons. It is against the law for anyone with less training than a nurse to dispense drugs from the medicine [sic] closet. Whenever a nurse is around she is the one who distributes the medication. But often and on a regular basis attendants or matrons ( a matron is in charge of a building) will distribute it. One attendant who does not distribute drugs did me a favor and copied down the list of drugs and dosages in the medecine [sic] closet of one of the buildings. There were over 34 drugs. Almost all of them only available by prescription. I showed the list to a prominent Waltham physician. He said that all of them were poisonous, many narcotic, and all marketable on the black market. This attendant who has no training had the time to copy the names and dosages of 34 drugs without anyone knowing of it. If he had time to do that he had time to steal them. There have been some reports of drugs missing. But not as many as there could be.

Perhaps the most frightening thing I heard was an incident when an experienced attendant was training a new attendant how to distribute drugs. She told the new attendant to double the dosage on the instruction card written up by the nurse. The experienced attendant said the nurse didn't know about the change and that it had simply been instituted by the attendants.

What records the school keeps are incomplete and it is hard for attendants to get to them to find out what illnesses the residents may have. In some wards there are many epileptics and diabetics. Little personal attention is paid to their conditions. The matrons and attendants may not even be able to tell which residents are ill. Consequently many diabetics are given the wrong kind of food and epileptics with subtle types of seizures may go unnoticed for years.

The hospital, which is one of the joys of the administration, is accredited by the American Medical Association, the College of Surgeons, and other medical organizations. It is often impersonal and inhuman in its treatment of residents. One resident has a condition that can be cured by an operation. A doctor told an attendant that the hospital, which is specifically for the mentally retarded, would not admit this particular person because he was too severely retarded. The doctor also said that a normal person could not endure the amount of pain caused by the condition and told the attendant to handle the resident very carefully because if he were jolted too hard or hit in the right place he would hemorrhage to death immediately.

Below is another of the incidents that were reported to me.

An attendant is speaking: "She (the resident) tripped and hit her skull on the concrete ridge that seperates [sic] the shower from the rest of the bathroom. She had a very very bad gash in her head and we took her to the hospital right away. They called the doctor immediately but we waited about forty-five minutes. She was lying there and they were holding something against her head to keep her from bleeding. We were restraining her because she was trying to get to get away. The doctor finally showed up and he took his sweet time about it. After he came in he talked and talked and talked about another half hour. All this time she was lying there and she hadn't been given anything. She was still bleeding and he was just talking about anything you could imagine: the conditions of the hospitals in France, everything that was missing in the hospital at the Fernald school. He kept talking but he didn't make a move. Finally another doctor walked in and between the two of them they managed to stitch her up.”

A member of the medical board of examiners for the area that includes Fernald said that this incident was grounds for an investigation. In some of the better buildings the attendants are afraid to send residents to the hospital because of the rough treatment they receive [sic]. These examples are not the worst that were told me. They are incidents where I am sure of ill treatment. They are fairly typical of what I heard about the hospital. I heard very little that was good.

There are other things about the physical plant that need improvement. Some of the buildings are over one hundred years old and are falling apart. The maintenance department is slow and often inefficient. There are insects, flies, roaches, Japanese waterbugs, etc in most of the buildings. Even the new ones have roaches and flies. Some of the buildings have mice.

The most important fact, however, is that the provisions for the maintenance of the physical existence of the residents are impersonal and dehumanizing.

In the past the administration of the school has not let the parents and families of the residents know of their relatives’ lives. Most wards have a special room for company clothes. Only recently have these clothes been given to some residents for daily wear. For most, and in the past they were reserved exclusively for when the resident had visitors. The families were either not shown the wards at all or shown them on special days when the attendants could get everything cleaned up. Recently the families of the residents of one building were given a more complete view and told they could tour the wards if they wished. The reported response was, "Won't we be disturbing the activities?" The attendants who told me this thought it very funny because until recently there had been no activities in that building and at the present time the amount of activity is insufficient. Parents should demand to be shown the ward at a time of their own choosing and not give the administration any warning.

Not every ward at Fernald is as bad as those that have been described here. There are some very good wards. But they should be the norm and not the exception. They don’t mitigate the fact that hundreds of residents live in psychologically debilitating conditions.

There has been a lot of progress at Fernald in recent years. Obviously it has not been enough. There are new programs and new grants. In three years most of the residents described in this article will be in "cottages" that the administration says will utilize modern conceptions of care for the mentally retarded. There is a new organizational set up called unitization going into effect at the present time. It is designed to bring professionals closer to the attendants. These programs are very fine but their effects on the residents can be only minimal unless there are more attendants. Unless there are people to give the residents personal attention, stimulation and affection the expertise of the professionals will be wasted. Neither the attendants nor the residents will be in a position to take full advantage of it. If there aren't more attendants the cottages will be more isolated and less well staffed than the wards in the large buildings.

We need to shift the emphasis of care for the mentally retarded onto a more personal basis. The whole system needs to be reoriented. More attendants must be hired. All attendants must be taught that their job is not merely to care for the bodies of the residents but to allow their minds to grow to the fullest extent. We must give the attendants professional guidance and more materials. We must provide individual psychological care for the residents who need it. All services for the residents, medical services especially, should be geared to treating them as special human beings.

For all of this we must look to the state legislature. Fernald is a state institution. More money and new positions must be authorized by the state. The legislature must decide if money is available to remedy these conditions. The money is there. We are a wealthy nation and Massachusetts a wealthy state. It is a question of priorities. Should there be more taxes, should other programs like building roads be sacrificed or should we let these conditions remain.

To say that it is the responsibility of the legislature to decide priorities is to a large extent saying it is the responsibility of the people of the commonwealth. The voters too must decide priorities. They must decide between paying more taxes, sacrificing a program that might be beneficial to them or allowing these people to continue living the way they do.

--

End of Transcript

For much of the existence of the Fernald School and similar institutions across the United States, its residents were called inmates on U.S. Census filings and other documents. This only changed in the 1970s with changes in the interpretation of federal law and the increased use of the term “resident.”