The Disabled Inmates Who Dared to Escape (Part II)

The empowering idea of escape. The unsettling truths of disappearance.

Listen to this week’s issue here:

The first part of this series explored how the non-disabled have created powerful beliefs about disabled people, beliefs that explain why they often respond so harshly when disabled people try to live full lives, freely and equally, out in the open. One of those beliefs is that disabled people are in need of forms of care that they do not understand and have no right to contest. Another is that disabled people have an innate propensity—a disability in its own right—for mischief and violence.

We can see these beliefs at work by looking at instances where the non-disabled try to impose them on the disabled and meet with resistance. Today, this happens in parks, on subways, and in street tents all over America. In our history, we can see it when we look at instances where intellectually and developmentally disabled people escaped from large-scale state schools; institutions that claimed to offer care but actually offered brutal conditions.

It can feel empowering to read accounts of intellectually and developmentally disabled people escaping the horror of institutions and wandering off into freedom. In our unhidden history there are instances of people changing their names or slipping across state lines into a history of their own making. There are even instances, as today’s images show, of institutional staff helping inmates escape, and of inmates simply walking out the door, never to return.

But escape is dangerous territory in its own right, in part because an element of escape is the act of disappearing. This week’s images explore the unsettling fact that not all forms of disappearance are the same. Some are stories of bravery and inspiration. Others suggest that we have an unspoken history that has allowed for violence against the disabled to flourish.

A note about redaction: Many of the documents below are drawn from archives in Massachusetts, where state laws are highly restrictive even when the people named died more than a century ago. Their names and certain identifying information are redacted.

“On escape (not paroled)” - 1923

Lincoln State School and Colony

Lincoln, Illinois

Instead of building fences around institutions for the feeble-minded (a loose, archaic term for intellectual and developmental disability), many states built their institutional schools in rural locations on vast plots of land. This made any attempt to escape more difficult. It also meant that institutions, which were filled with imprisoned populations of disabled child inmates, were particularly attractive to predators.

Moreover, the size of institutional inmate populations (more than 2,200 people in the 1923 annual report from the Lincoln State School pictured above) made it impossible for superintendents to keep accurate records at all times. This made it easy for an inmate to disappear and go unaccounted for, especially in summer months, when institutional leaders were often away.

That’s why runaway figures like the one pictured here are a growing source of concern for researchers. While these figures may represent inmates who successfully fled, the extraordinarily high rates of violence against disabled people today, coupled with historical evidence of widespread murder and abuse in and outside of institutions, suggests that these lists may also reflect inmates who were disappeared; murdered by people who were attracted by vulnerable people, lax oversight, and isolated locations.

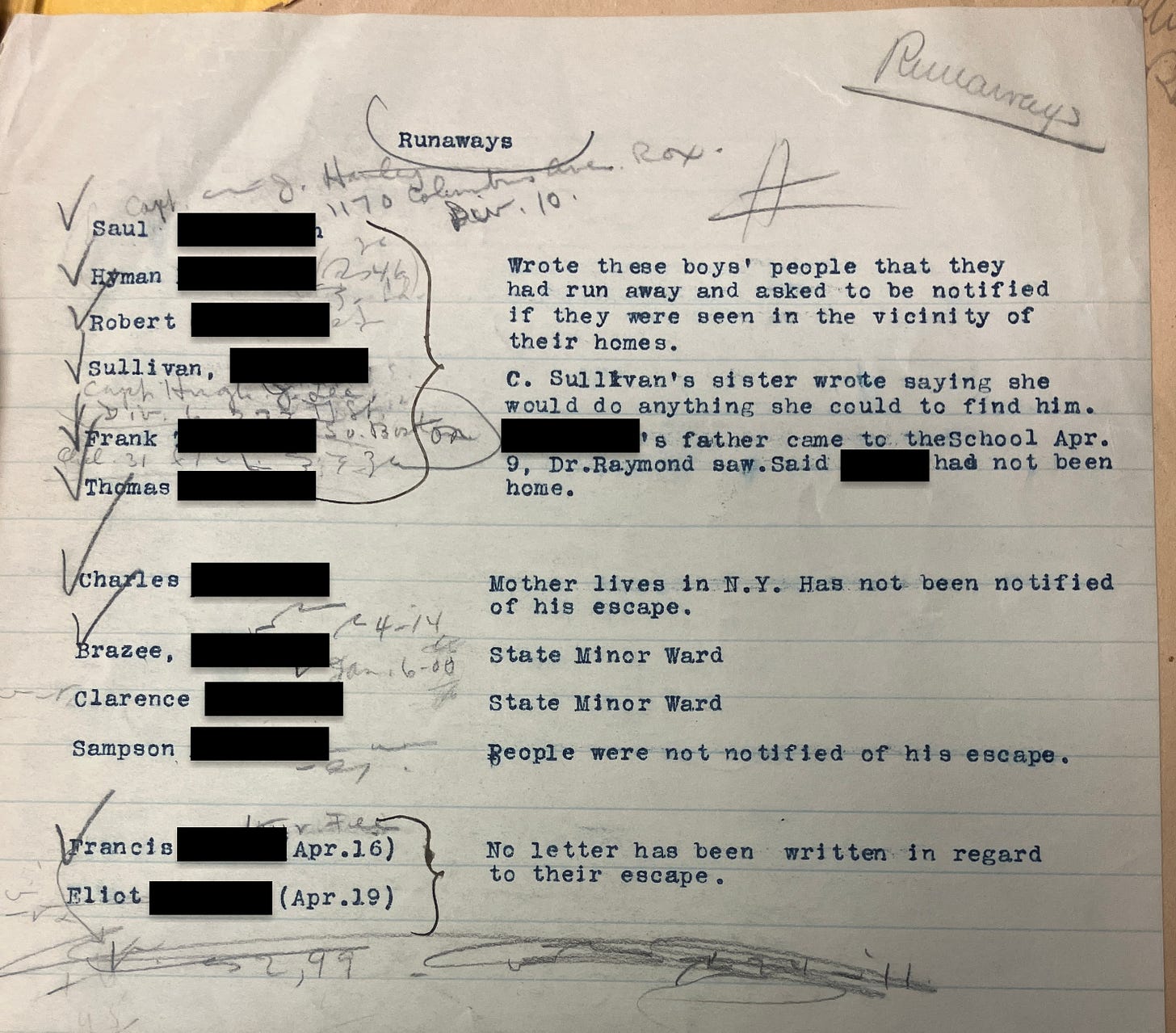

“People were not notified of his escape.” (1917)

Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded

Waltham, Massachusetts

Intellectually and developmentally disabled people were forcibly committed to state schools by authorities, but some were also voluntarily committed by family members who believed their loved ones would receive an education. Where this was the case, this document from the Massachusetts School shows that family members were not notified of disappearances and were concerned for the whereabouts of their kin. The lack of any similar notation for those who were “state minor wards” and had no known family on record, is striking.

As part one of this series showed, the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded would pay people who captured escapees, but the school also had a policy of not sending its employees to pursue escapees. While seemingly-liberal, this made it all-the-more possible for disappearances of another kind to be written-off as escapes.

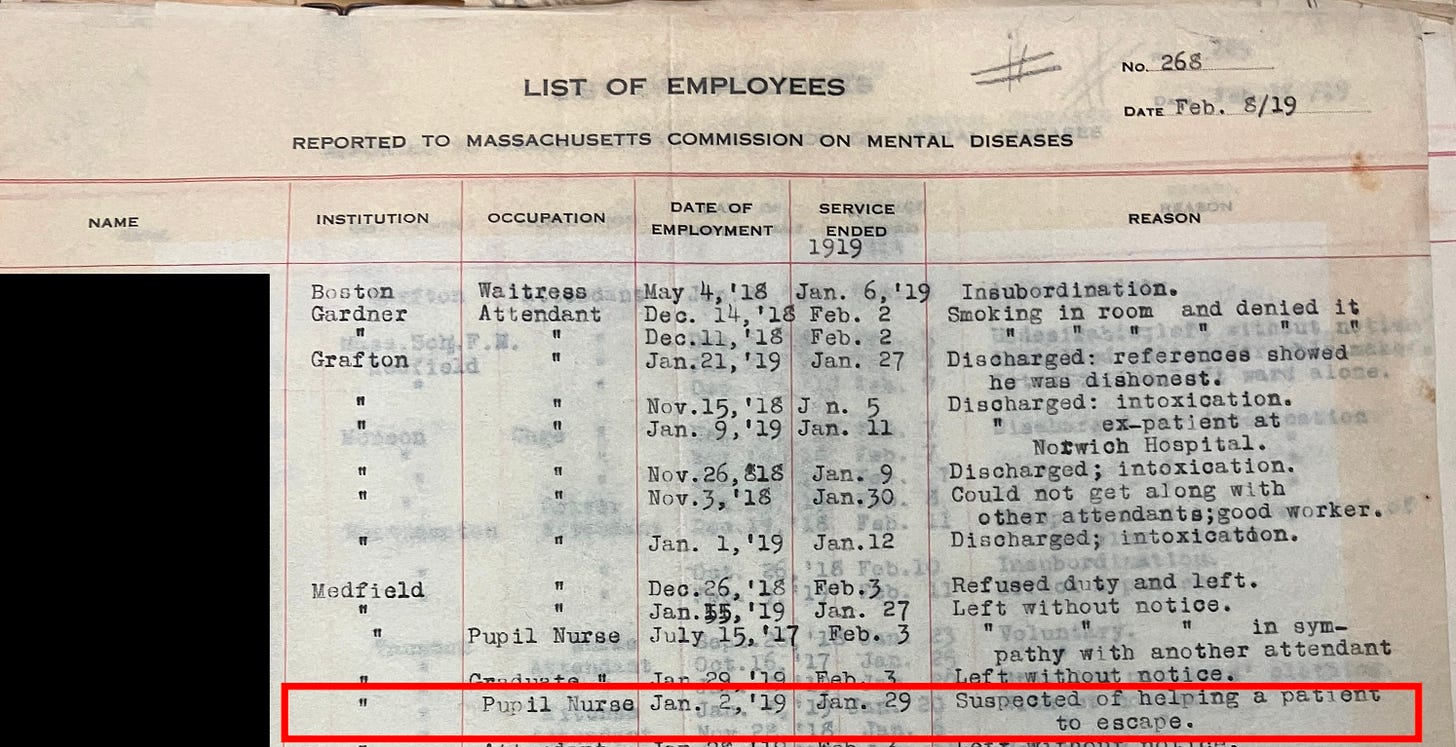

“Suspected of helping a patient to escape” (1919)

Medfied State Hospital (Asylum)

Medfield, Massachusetts

Abuses were prevalent in state institutions, and did not always go unpunished. While institutional leaders almost never questioned the root cause—institutionalization itself—countless employees were dismissed for infractions, ranging from intoxication to abuse. Some employees reported what they saw to their superiors. Others, like the pupil nurse described here, took matters into their own hands. She was fired in the winter of 1919 on suspicion of having assisted an inmate’s escape from the state hospital asylum in Medfield, Massachusetts.

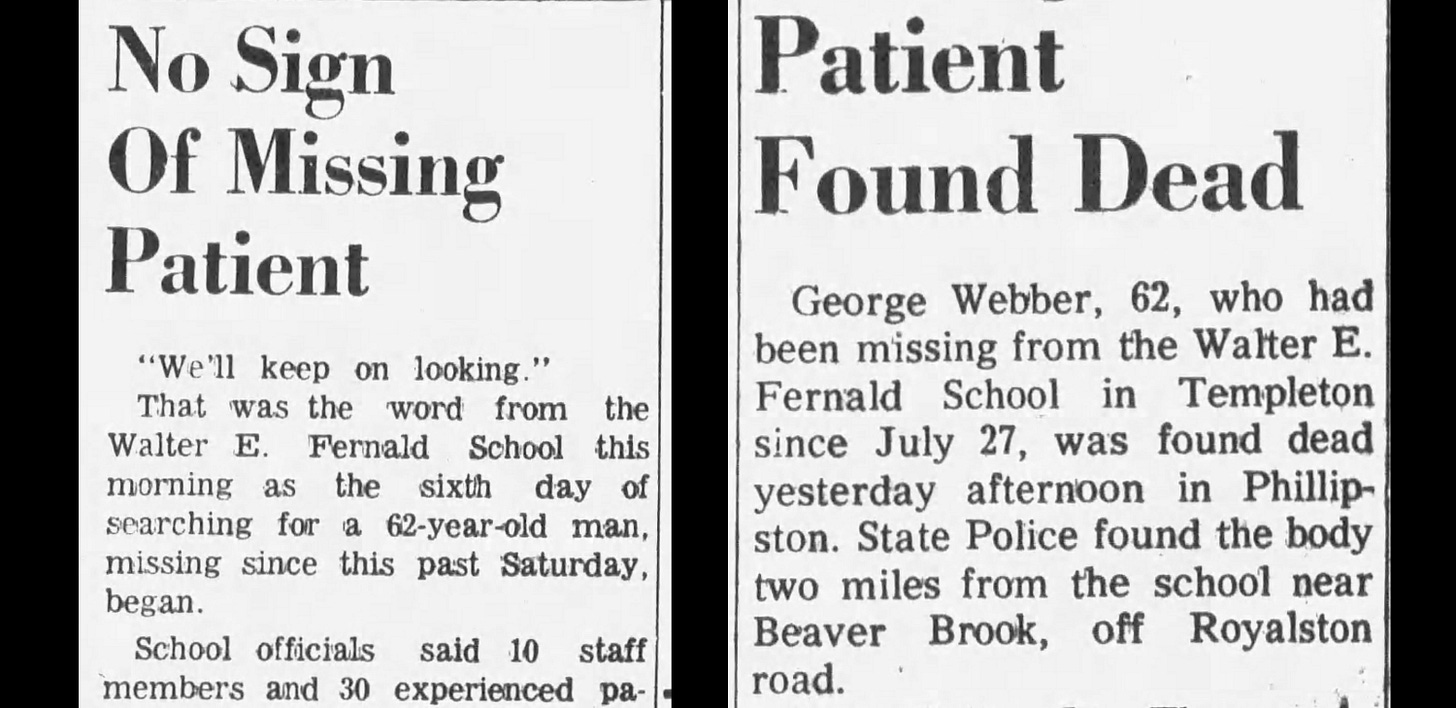

“Webber may have left the area” (1963)

Templeton Colony, Walter E. Fernald State School

Templeton, Massachusetts

George William Tristan Webber was born on March 29, 1901, in Beverly, Mass. to Franklin J. and Pauline A. Webber (née Rich). At the age of 5 he was committed to the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded, later renamed the Walter E. Fernald State School, which operated a 1,600 acre work farm in the woods of north-central Massachusetts. For a period in his childhood, Webber appears to have been released from the institution, but he was later recommitted. By the time he went missing in July 1963 at the age of 62, he had disappeared from the lives of any remaining family members. For that reason, it is particularly bizarre that the school called off its search because, as they told The Athol Daily News, they believed “Webber may have left the area.” Webber’s body was found on December 7, months after his disappearance. No autopsy was conducted and his cause of death was listed as “probably natural causes.” He was buried in the woods of Waltham in an institutional grave under a cinder block marked P-123.

“Method of Escape: Front Door” (1970)

Walter E. Fernald State School

Waltham, Massachusetts

This record from 1970 shows how one man, raised in the Walter E. Fernald State School, decided to escape and walked out the front door into a world he had been raised without knowing. Only after his escape did the institution chase him down and provide him with newly emerging social services, likely because it was easier than returning him to an already overcrowded institution that held more than 2,500 inmates.

In 1972, two years after the man escaped, Superintendent Malcolm Farrell wrote to congratulate him on his success in living independently. “I understand from your social worker…that you have made an excellent adjustment to community living, that you have two jobs and an apartment of your own,” Farrell wrote. “I am happy to notify you of your discharge from the Walter E. Fernald School effective February 29, 1972.”

The third and final part of this series will connect the stories of institutionalization, escape, and violence to a broader unhidden history. While this series will draw to a close, (Un)Hidden will return to these themes time and again in different ways, because this history refutes one of the most commonly used excuses for using state resources to commit violence against the disabled in the present day: that we are in a unique moment where the burden of the disabled on society is too extraordinary to call for anything but institutionalization and violence.